Welcome to the site which examines the events, issues and personalities of Edward II's reign, 1307-1327.

Pages

20 December, 2006

Merry Christmas!

Before I go, just a few words on Edward II's Christmases. It was his custom to play dice on Christmas night, and in 1316, at Clipstone in Nottinghamshire, used up the large sum of five pounds playing (the King was an inveterate gambler.)

Edward enjoyed the tradition of the "King of the Bean" or the Lord of Misrule, on Twelfth Night. In 1317, he gave that year's King, William de la Bech, "a silver-gilt chased basin, with ewer to match", and the next year, to Thomas de Weston, a squre of his household, "a silver-gilt basin with stand and cover, and a silver-gilt pitcher to match".

In 1317, Edward had a "great wooden table" placed in the Great Hall of Westminster Palace just in time for Christmas, and around the same time took possession of a "great hanging of wool, woven with figures of the King and Earls upon it" with "a border of green cloth round the said hanging, for saving the same from being damaged in hanging it up." At Christmas/New Year 1311/12, Queen Isabella sent out gifts of wild boar meat and Brie to, among others, the Earls of Lancaster and Hereford and Piers Gaveston's wife Margaret, and there are records of the "sumptuous gifts of plate" Edward gave to friends and household knights.

If you're interested in how Christmas and New Year were celebrated in the Middle Ages, here's a handful of sites (there are plenty more):

Christmas Traditions In England During the Middle Ages

Medieval Christmas

Tales of the Middle Ages - Christmas

Have a very merry Christmas and a happy New Year, everybody!

17 December, 2006

The Childhood of Edward II

Edward’s first nurse was the Welshwoman Mary, or Mariota, Maunsel, who fell ill and was replaced by Alice de Leygrave in the summer of 1284, when Edward was taken from Caernarfon to Chester. Although she had only looked after him for the first few months of his life, Edward never forgot about Mary. In 1307, he gave her 73 acres of land, to hold rent-free for the rest of her life, and in 1312, granted her a hundred shillings per year for life 'out of the yearly issues of the king's mills at Karnarvan'. Alice de Leygrave and her daughter Cecily later joined Queen Isabella’s household as damsels, and Edward also granted them and other family members land and favours. Alice was described in a document of 1313 as "the king's mother...who suckled him in his youth."

In April 1284, the heir to the throne was Edward’s brother Alfonso, born in November 1273 and thus ten and a half when his little brother was born. The King and Queen had already lost two sons (John, aged five, in 1271 and Henry, aged six, in 1274) but Alfonso seems to have been healthy – his marriage to Margarete, daughter of Count Floris V of Holland, was being arranged this year, and the Alfonso Psalter was in preparation, presumably to celebrate the wedding. His death on 19 August 1284 seems to have come out of the blue and been a terrible shock, not only to his parents, but to the country as a whole – the populace was used to thinking of him as their future king. (it’s worth bearing in mind that if he had lived to become king, ‘Alfonso’ would be a common English name!)

At the age of not quite four months, Edward became heir to the throne. Little is known about his early life, but he had his own household from a very young age, as was common for royal boys. His sisters, or some of them, presumably lived with him, but as heir to the throne, Edward was the centre of the household. He lived most of the time at Langley, near St Albans (known since 1428 as King's Langley), which his mother Queen Eleanor held of the king’s cousin, Earl Edmund of Cornwall, and which was granted to Edward himself in 1302. Langley was a manor house on a hill, attractively arranged around three courtyards.

Edward's tutor was Sir Guy Ferre, who seems to have failed to impose any discipline on Edward - he went to bed when he liked, developed a taste for gambling, and - more significantly - a predilection for 'peasant' activities such as digging, thatching and shoeing horses, which would earn him huge censure later in life.

Just past his second birthday, in May 1286, his parents departed England for Gascony, which was ruled by the English crown. They would not return for more than three years - which had a huge impact on the young Edward's relationship with his parents. Fifteen months after their return, Queen Eleanor was dead, and King Edward I gradually became an increasingly remote and terrifying figure. Without wanting to be too psychoanalytical, Edward's whole life shows his desperate need to love and be loved, probably because of the lack of parental affection in his childhood.

In July 1289, the five-year-old Edward was taken, with four of his five sisters, to Dover to greet their parents on their return from Gascony. The sisters were: Eleanor, aged 20; Joan, aged 17; Margaret, aged 14; and Elizabeth, aged almost 7. The missing sister was Mary, aged 10, who was at Amesbury Priory with the children’s grandmother, Queen Eleanor of Provence. It must have been a nerve-racking occasion for the little boy, to meet the formidable parents he surely couldn’t remember. As the heir to the throne, he was more important than his older sisters, and one imagines that the king examined his only surviving son anxiously. There were few concerns, however; Edward, as he would remain all his life, was a healthy, sturdy boy.

Edward I started to make arrangements for Edward’s marriage - an issue of great importance. (See my previous post on the Maid of Norway). He also started marrying off his daughters. On 28 November 1290, a couple of months after the death of the little Maid, Queen Eleanor died suddenly in Harby, Notts. She was in her late forties. Edward, as her only surviving son, inherited her lands and became Count of Ponthieu and Montreuil at the age of six.

A few months later, on 26 June 1291, his grandmother Eleanor of Provence also died, in her late sixties. Eleanor was the widow of Henry III, who had died in 1272. For all her faults, Queen Eleanor was a devoted mother and grandmother, always concerned about her grandchildren, and her death deprived little Edward of a kindly, affectionate figure who always did her best for him. On 1 September 1290, she sent a letter to her son, Edward I, who was planning to take his six-year-old son to the north (presumably to meet the Maid on her arrival in Scotland, though that's not certain):

"We feel uneasy about his going. When we were there, we could not avoid being ill, on account of the bad climate. We pray you therefore, deign to provide some place in the south, where he can have a good and temperate climate, and dwell there while you visit the north."

1290 and 1291, in fact, were bad years for Edward and his family relations. His mother and grandmother died, his sisters Joan and Margaret married, another sister, Mary, was veiled as a nun. In 1293, his eldest sister Eleanor finally married too. The remaining sister, Elizabeth, who was only twenty months older than Edward, probably stayed at Langley with him until her own wedding in February 1297.

It's possible that her future husband Jan, son and heir of Count Floris V of Holland (Jan’s sister Margarete had been betrothed to Alfonso) also lived with them at Langley. Jan was born sometime in 1284, so was the same age as Edward, and grew up in England. He succeeded his father in June 1296, and returned to England in early 1297 to marry Elizabeth. She was fourteen and a half, and he twelve. Always a sickly youth, he died in 1299, childless.

Later in the 1290s, ten boys were placed in Edward's household as his companions and royal wards, or pueri in custodia, accompanied by their tutors. Hugh le Despenser the younger was one. Another was Piers Gaveston, who was placed in Edward’s household sometime at the end of the 1290s – a fateful decision by King Edward I. The Gavestons or Gabestons were minor nobility from Gascony (Piers was emphatically not a peasant and Edward's 'bit of rough', as he's often portrayed) and the family of Piers' mother, Claramunde de Marsan, were landowners in Bearn. His father Arnaud's tomb in Winchester Cathedral still exists. Piers was probably a year or two older than Edward, handsome, athletic, witty and a great jouster and soldier. Edward fell deeply in love.

The records for Edward’s household still survive for the year 1292/93, when he was eight/nine years old. They show that he lived at Langley from 23 November 1292 to 13 April 1293, then went on a typical 'royal progress' across Southern England, staying one or two nights in each place - the enormous size of his household, hundreds of people, meant that longer stays were generally not welcomed by the local populace. In 1294, the Dunstable annalist commented about Edward: "Whatever he spent on himself and his followers, he took without paying for it. His officials carried off all the victuals that came to market...not only whatever was for sale, but even things not for sale..." It's worth remembering that Edward was barely ten years old at the time!

Edward spent eight nights in Bristol in late September 1293 for his eldest sister Eleanor’s wedding to Count Henri III of Bar (they then stayed with him for a few weeks before travelling to Bar) His cousins Thomas and Henry of Lancaster - sons of Edward I's brother, Earl Edmund of Lancaster - stayed with him for a few days in June 1293. They were about three and six years his senior, so about twelve and fifteen, and brought a large retinue with them, who had to be fed at the expense of Edward's household. Also in their company was the future Duke Jan II of Brabant, who was eighteen in 1293 and had married Edward’s sister Margaret in 1290. Jan also grew up at the English court, and lived in England till his father died in the spring of 1294 (at a tournament in Bar, arranged by Count Henri to celebrate his marriage to Eleanor). All together, the three young men brought sixty horses and forty-three grooms, and Edward's clerk (who recorded the expenses) fumed over it. Every day, he wrote "They are still here" and on the last day "Here they are still. And this day is burdensome...because strangers joined them in large numbers".

As he gew older, Edward spent more and more time with his father, often in Scotland. He took part in the siege of Caerlaverock in 1300, when he was sixteen. The herald-poet wrote of Edward in the Caerlaverock Roll of Arms: "...He was of a well proportioned and handsome person/Of a courteous disposition, and well bred". On 7 February 1301, still aged sixteen, Edward was created Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester, during Parliament at Lincoln. This was a huge territorial endowment, composed of all the royal lands in Wales and the rich lands of the earldom of Chester. Edward, Prince of Wales, Earl of Chester, Count of Ponthieu and Montreuil, was now a great feudal magnate in his own right; and his lonely childhood was over.

10 December, 2006

Women of Edward II's reign: Eleanor de Clare

Eleanor was born in the great castle built by her father, Caerphilly in Glamorgan, in October or November 1292. Her mother was Joan of Acre, the second oldest of Edward I's five surviving daughters, and her father was Gilbert 'the Red' de Clare, earl of Gloucester and Hertford. Joan was twenty at the time of Eleanor's birth, Gilbert forty-nine. Eleanor was Edward I's eldest granddaughter, and about eighteen months younger than her brother Gilbert, future earl of Gloucester. She had two younger sisters: Margaret, probably born in the first half of 1294 and the wife of Piers Gaveston, and Elizabeth, born in September 1295. Eleanor was only eight and a half years younger than her uncle Edward II.

Little is known about the childhood of the Clare sisters. Their brother Gilbert grew up, after 1299, in the household of their step-grandmother Queen Margaret, who was probably only about nine years older than Gilbert. Their father Gilbert the Red died in December 1295 at the age of fifty-two, only a few weeks after the birth of his youngest child Elizabeth, and in 1296, the widowed Joan was assigned Bristol Castle as a residence for her children. In early 1297, when Eleanor was four, Joan married her husband's squire Ralph de Monthermer, without her father's consent; he was hoping to marry her to the count of Savoy. Joan is supposed to have taken her young children with her to plead her case to her father, presumably hoping that the presence of his young grandchildren would persuade the king to be lenient. It didn't work, and de Monthermer was imprisoned for a time, although Edward I finally had to accept the inevitable, as he couldn't unmarry the couple.

At the age of thirteen and a half, Eleanor was married to Hugh le Despenser the Younger. Their wedding took place on 26 May 1306 at Westminster, in the presence of the king. Queen Margaret was probably not present, as she had given birth to the king's youngest child - another Eleanor - several weeks earlier. The king was close to sixty-seven and would die just over a year later. (Little Eleanor, Eleanor de Clare's aunt, died at the age of five in 1311.) Eleanor's mother Joan of Acre was surely present; she had another eleven months to live. I don't know if Hugh le Despenser's mother Isabel Beauchamp, daughter of the earl of Warwick, witnessed the wedding; she died a mere four days later. Another guest was Eleanor's uncle, the future Edward II, who had been knighted with Hugh (and almost 300 others) four days earlier. Already Prince of Wales, earl of Chester and count of Ponthieu and Montreuil, he was created duke of Aquitaine at this time. His beloved companion Piers Gaveston was knighted on the day of Hugh and Eleanor's wedding.

Hugh, who was somewhere in his late teens, was hardly a brilliant match for the king's eldest granddaughter. Although he was an earl's grandson, the step-grandson of another earl (Norfolk, who died this year) and brother-in-law of the king's nephew Henry of Lancaster, he had no hope of inheriting a title. His father's lands, mostly in the Midlands and Buckinghamshire, were extensive, but until the elder Hugh died, Hugh could expect to hold practically no land. Edward II gave him the former Templar manor of Sutton in Norfolk in 1309, his only gift to Hugh before he became royal favourite. In 1310, Hugh the Elder handed over half a dozen manors to his son, who evidently lived in somewhat straitened circumstances.

In an age where land was power, Hugh was a nonentity, which limited Eleanor's own influence. However, she was a familiar face at court, where she often attended Queen Isabella as lady-in-waiting, accompanying her on the royal trip to France in 1313. Isabella, Eleanor's aunt by marriage though several years younger, had a group of noblewomen who attended her on a rota basis, as they all had husbands and families and feudal responsibilities of their own. Eleanor had her own retinue, headed by her chamberlain John de Berkhamsted.

Away from court, her relationship with Hugh was pretty successful, to judge by the large number of children they had together. She was also close to her uncle Edward II, who paid all her expenses when she was at court, and even sometimes when she wasn't - a privilege not extended to his other nieces. She appears in contemporary documents as 'Lady Alianore le Despenser'. Edward's affection for her did not, however, extend to her husband at this time.

Eleanor and Hugh's lives changed completely when her brother Gilbert, earl of Gloucester was killed at the battle of Bannockburn in June 1314, when he was twenty-three. Eleanor's second cousin, Robert Bruce, king of Scotland, kept an overnight vigil over Gloucester's body, and sent it back to England with full honours and without demanding payment for it, as he was entitled to do. Gloucester's widow Matilda - sister of Robert Bruce's queen, Elizabeth - claimed to be pregnant, a pretence she kept up for a full three years. (Honestly, you couldn't make this up.) Her motives are obscure; perhaps she miscarried and couldn't accept it. Edward II was happy to support this pretence; the Gloucester lordship was extremely rich and he would have been much happier if Gloucester's son had inherited the lot. As things stood, though, Gloucester's three sisters were equal heirs to the inheritance. Under medieval law, sisters inherited equally; the law of primogeniture applied only to men.

Finally, in 1317, the lands were divided. Countess Matilda had earlier been assigned her widow's dower, one third of the lands, which would be divided out among the three sisters when she died in 1320. Hugh and Eleanor's share was Glamorgan, and a few manors in England. Her younger sisters were by this time married to men Edward II trusted, Margaret to Hugh Audley and Elizabeth to Roger Damory; Audley and Damory were thereby catapulted to wealth and huge influence. The division of the Clare lands can be seen as one of the most significant events of Edward's reign, as Hugh le Despenser, ambitious and unscrupulous, used Eleanor's inheritance to force himself into power. He was chosen as Edward's chamberlain in 1318, used this proximity to the king to make Edward infatuated with him, and attempted to take over the entire Clare inheritance in South Wales.

The story of Hugh's rise to power has been told many times, so I won't repeat it here. The great Edward II historian J.R.S. Phillips has described him as the "classic example of a man on the make who succeeded in making it". It's a shame that we have no idea what Eleanor thought of her husband's misdeeds, his extortion of lands and property including some that belonged to Eleanor's sister Elizabeth, and his relationship with her uncle. That Hugh was Edward's lover seems 99% sure to me; Edward was infatuated with him. However, Hugh and Eleanor's sexual relationship also continued, as a few of their children were born after the start of Hugh's relationship with Edward.

There are even hints that Eleanor herself was involved in a sexual relationship with her uncle. This is stated directly in the Chronographia Regum Francorum, and the two are oddly linked in a document of the 1320s which mentions medicines bought for them 'when they were ill'. Edward sent her many presents, and after one short visit gave her the substantial sum of a hundred pounds. This was approximately half of Hugh and Eleanor's annual income prior to her brother's death. It has been postulated that the chronicler who castigates Edward for his 'sinful and illicit unions' had Edward's affair with his niece Eleanor in mind, rather than - or as well as - his sexual relationships with other men. However, this affair is far from certain, and in the absence of firm evidence we should give Edward and Eleanor the benefit of the doubt.

Edward II and Hugh definitely trusted Eleanor, however. In 1324 she was put in charge of the household of John of Eltham, Edward and Isabella's younger son, and it's often stated that she was put in Isabella's household as a 'housekeeper', or rather spy, with permission to read all Isabella's correspondence and keep an eye on her. Edward and Isabella's relationship had spectactularly deteriorated by 1324, and, sliding into war with her native France, Edward didn't trust her at all. However, I'm not sure how Eleanor is meant to have watched Isabella day and night - as she's alleged to have done - and also been in charge of Isabella's son somewhere away from the 'long-suffering' queen.

In 1326, Hugh and Edward II suffered the inevitable consequences of their tyranny, and fell from power. How Eleanor felt about the hideous death of her husband of twenty years can only be surmised. Whether she was a willing participant in Hugh's misdeeds, or if she had ever tried to mitigate Hugh's harshness, is unknown; if she did try, she was apparently unsuccessful. Perhaps she loved him; later, she had a splendid tomb built for him at Tewkesbury Abbey. In October 1326, she was in the Tower of London with her ten-year-old cousin John of Eltham, who had been left by his father the king in nominal charge of London. She surrendered the Tower to the mob, and was imprisoned there, for two years. Three of her daughters were taken from her and forcibly veiled, and her eldest son was imprisoned until 1331. Later, she lost her lands; Glamorgan was given to Edward III's queen, Philippa, although Edward III restored them to her after the downfall of his mother and Roger Mortimer.

In early 1329, Eleanor was abducted from Hanley Castle, Worcestershire, by William la Zouche, and married to him. Zouche was a distant cousin of Roger Mortimer, and was one of the men who arrested Hugh le Despenser in South Wales. He also besieged Eleanor's teenaged son at Caerphilly in late 1326/early 1327. Whether Eleanor consented to the marriage is unknown, but it was a fairly common problem for the Clare women, because of their huge wealth. In 1316 her sister Elizabeth was abducted and married to Theobald de Verdon, and in the 1330s Eleanor's niece Margaret Audley, daughter of her sister Margaret, suffered the same fate when she was taken by Ralph Stafford. Eleanor, who was thirty-six in early 1329, bore a son, also William, to her second husband. He was her tenth or eleventh child, and became a monk at Glastonbury Abbey.

Eleanor outlived her second husband, and died in June 1337 at the age of forty-four. She is buried at Tewkesbury Abbey, with many of her ancestors and descendants; she and Hugh le Despenser, and their son Hugh the Even Younger, were major benefactors of the abbey. Eleanor's fascinating life is the subject of Susan Higginbotham's novel, The Traitor's Wife.

03 December, 2006

Blog Birthday, and Betrothals

This post is about Edward II's betrothals before Isabella; the women he might have married had things turned out differently. The first of these was Margaret, the 'Maid of Norway'.

A little background information: Alexander III ascended the throne of Scotland in 1249, aged not quite eight. In 1251, he married Margaret, daughter of Henry III of England; she was almost exactly a year his senior. The couple had three children: Margaret, 1260-1283, Alexander 1264-1284, and David, 1272-1281. Queen Margaret died in 1275. Young Alexander married (yet another) Margaret, daughter of the count of Flanders, in 1282, but had no children. King Alexander's daughter married Erik II, King of Norway, in 1281. (He was known as 'Erik the Priest-Hater'; I love that!) Oddly, he was thirteen and she was twenty-one. Margaret gave birth to the couple's only child, a daughter inevitably named Margaret, and died around 9 April 1283, possibly in childbirth.

In March 1286, King Alexander III died in a bizarre accident when he rode his horse off an embankment in the dark; his body was found the next day. All three of his children had pre-deceased him, and although his second wife Yolande de Dreux was pregnant, her child was stillborn in November 1286. The Guardians of Scotland ruled Scotland during this time. The Queen of Scotland was now little Margaret, the Maid of Norway, aged three - Alexander III's granddaughter and only living descendant. She was known as “dame Margarete Reyne de Escoce” (Lady Margaret, Queen of Scotland).

In 1289 and 1290, King Erik, the Guardians and Edward I of England - brother-in-law of Alexander III and great-uncle of the Maid - signed treaties agreeing to the marriage of the Maid to King Edward's only surviving son, the future Edward II. Lord Edward was six in 1290, a little younger than his intended wife, and a papal dispensation had to be obtained for the marriage, as they were first cousins once removed (Margaret was the great-granddaughter of Henry III, Edward his grandson).

Edward I intended his son to rule Scotland in right of his wife, as well as England (of course, it turned out that Edward II couldn't even rule one country, never mind two, but that probably wasn't obvious when he was only six). In 1284, on the death of his son, Alexander III had signed a treaty with the earls and barons of Scotland that acknowledged the Maid as his heir, but he almost certainly intended her to reign jointly with her future husband, rather than as sole Queen Regnant.

During the summer of 1290, Edward I prepared two ships at Great Yarmouth and sent them to collect the little Queen from Norway. One was loaded with casks of wine, the other with meat, fish, sugar, spices, wine, beer, peas, beans and nuts. Margaret boarded one of the ships to be taken to her new home, but unfortunately for Scotland and the plans of Edward I, she died in the Orkneys shortly after her arrival there. She was seven years old, the Queen who never laid eyes on her kingdom (the Orkneys belonged to Norway at this time). Her body was taken back to Norway, and buried in Bergen, next to her mother. No less than thirteen men arose to claim the throne of Scotland.

It's really fascinating to contemplate what might have happened if the Maid had lived. Firstly, there would have been no Hundred Years War, at least not as we know it, as Edward II and Margaret's son (assuming they had one) would have had no claim to the French throne as Edward III did through his mother Isabella. Would England and Scotland really have been peacefully united three centuries earlier than really happened? And what about the conflicts Edward II had with his barons - would they have been lessened, with no need for Edward to fight in Scotland? And on a personal level, would the marriage of Edward and Margaret have been happier than Edward and Isabella's - and would Edward have ruled longer with no rebellion of Isabella and her lover Mortimer?

In 1294, Edward I arranged another betrothal for his son, with Philippa, daughter of Guy de Dampierre, count of Flanders. Little is known about Philippa, but she was probably a good bit older than Edward, who was ten in 1294; her parents were married in 1265. Her sister Margaret was married in 1282 to Alexander, son of Alexander III (see above. Incidentally, Margaret's son by her second marriage, Duke Reinald II of Guelders, married Edward II and Isabella's daughter Eleanor of Woodstock in 1332. He was almost thirty years her senior).

In February 1297, King Edward and Count Guy swore to uphold the marriage of their children(“covenances de faire mariage entre Edward nostre chere fiuz, e Phelippe fille au dit conte”). Now, however, her sister Isabella was mentioned as a possible substitute. The reason was that poor Philippa was now being held prisoner by Philip IV of France, who was determined that the match should not go ahead (for reasons too complicated to go into here, but there were huge tensions between Count Guy and King Philip, and King Edward was an ally of Guy). Philippa was held in Paris until her death in 1306. Edward I made peace with Philip in 1298 and abandoned Count Guy - and any idea of a marriage alliance between England and Flanders.

In 1299, Edward I and Philip IV signed a treaty, in an attempt to solve the long-standing conflicts between France and England. In September that year, Edward I married Marguerite, younger half-sister of Philip; Edward was now sixty and had been a widower for nine years. Marguerite's date of birth is not known, but might gave been as late as 1282, making her forty-three years younger than her husband and a mere two years older than his youngest child by Eleanor of Castile, Edward II.

Although a marriage between Marguerite and Edward II, instead of Edward I, was never suggested, I can't help wondering how different things might have been if they had married. She was closer to his age than her niece Isabella, and would probably have made him a more understanding and compassionate consort.

The treaty of 1299 also made provision for the marriage of Edward II and Isabella. She was the sixth of the seven children of Philip IV by Jeanne, Queen of Navarre, and her three elder brothers were all kings of France in turn; Louis X, Philip V and Charles IV. Isabella also had a younger brother, Robert, who was probably born in 1297; he died in July 1308, six months after Isabella married Edward II.

It's a little known fact that Isabella also had two elder sisters: Marguerite and Blanche. As with all Philip IV's children, with the exception of Louis X (who was born on 4 October 1289), their dates of birth are not known. Marguerite was the eldest daughter, born perhaps 1288 or 1290, and Blanche was probably born about 1293. The dates of their deaths are not known either, but both were certainly dead by 1299, or one of them may well have been betrothed to Edward II instead of Isabella. Probably Blanche, as Marguerite was promised in 1294 to Fernando IV, King of Castile. Again, it's interesting to consider whether Edward II's reign would have turned out differently; or would Isabella's elder sisters have taken the same actions that she did?

Isabella herself was probably born sometime between July 1295 and January 1296, so she was more than eleven years younger than Edward and only three years old when her marriage was arranged (Edward was fifteen). Their formal betrothal took place on 20 May 1303. On 27 November 1305, Pope Clement V, eager for the union of Edward and Isabella, and the peace between England and France he assumed would follow it, tried to arrange their proxy wedding. On this day, he signed a dispensation to allow Isabella to marry despite her young age - she was ten, or close to it, to Edward's twenty-one. On 3 December, in the presence of notaries at the Louvre, Isabella appointed her uncle Louis of Evreux to act as her proxy. However, King Edward rejected the proposal.

The wedding finally took place in Boulogne on 25 January 1308, six months after Edward II succeeded to the throne. He was twenty-three and nine months, Isabella almost certainly only twelve. Edward showed no interest in Isabella until years after the wedding - understandably - and even before it, never seems to have sent her any letters or gifts, though he communicated often with her uncle Louis of Evreux.

If Edward II had married another woman, would the rebellion of 1326 still have taken place, or something like it? Would Edward still have been forced to abdicate? Would the Hundred Years War have still taken place, if Edward II had lived to the 1340s? There's no way of knowing, but I find it fascinating to speculate...

29 November, 2006

The Execution of Roger Mortimer

Roger was born on the same day as Edward II, but three years later. Today marks the 676th anniversary of his execution at Tyburn, at the age of forty-three.

Roger was arrested in Nottingham Castle on 19 October 1330, in the hastily planned and executed seizure of power by the young Edward III, aged not quite eighteen. Apparently, Edward III wished to execute him immediately, but was persuaded by Henry, earl of Lancaster, to put Roger on trial before Parliament. Roger was first taken to Leicester, then imprisoned in the Tower of London until his trial on 26 November.

In keeping with several other so-called 'trials' of this time, of Thomas of Lancaster and the Despensers, Roger was not permitted to speak in his own defence when he was taken before Parliament at Westminster. In fact, he was gagged to make sure he couldn't speak. He was also bound, with ropes or chains. He was charged with fourteen crimes, including: the murder of Edward II; procuring the death of Edward's half-brother Kent; and taking royal power and using it to enrich himself, his children and his supporters.

The outcome of the 'trial' was never in doubt. Roger was found guilty of these crimes, and 'many others', by notoriety, that is, his crimes were 'notorious and known for their truth to you and all the realm'.

On 29 November 1330, Roger was taken from the Tower. He was forced to wear the black tunic he had worn to Edward II's funeral three years earlier, a pointed reference to his hypocrisy, and dragged behind two horses to Tyburn, where he would be hanged. His clothes were taken off him, so he died naked. Verses of the 52nd Psalm were read out loud to him - 'Why do you glory in mischief?' - and he was allowed to speak a few words to the crowd. He didn't mention Edward II, or Queen Isabella, but admitted his role in the judicial murder of the earl of Kent.

Roger was not, as is often stated, the first person to be executed at Tyburn (executions had taken place there for well over a century, since the 1190s), but he was the first nobleman to be hanged there. Tyburn was the execution site for common criminals, and hanging was the method used to dispatch them. Noblemen were usually beheaded. The Despensers were an exception, but in 1322 Edward II had commuted Thomas of Lancaster's sentence to be hanged, drawn and quartered to beheading, and in 1312 even Piers Gaveston was given the nobleman's death, because he was the earl of Gloucester's brother-in-law. The site and method chosen for Roger's execution were a deliberate attempt to treat him as a common criminal. At least Edward III spared him the full horrors of the traitor's death, and death came within a few minutes - a relief, as medieval hanging victims often took hours to die.

Roger's burial site is uncertain. He is stated to have been buried at the Grey Friars church in Shrewsbury, but a year after his death, his widow Joan de Geneville petitioned Edward III for his body to be removed to Wigmore, and it was the Franciscans of Coventry who were licensed to deliver it. Wherever his final resting place was, his tomb is now lost.

Unfortunately the story that, twenty-eight years later, Isabella chose to be buried at the Grey Friars in London because it was Roger's final resting place, is not true, though it's still often repeated today. It is possible, however, that Roger's body lay there for a while before his final burial, though this hardly seems sufficient reason for Isabella to have been buried there (her aunt Marguerite was also buried there, in 1318).

Roger Mortimer was a fascinating man who deserves to be much better known. He was intelligent, competent, and ruthless, and, in the end, proof of the adage that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Power went to his head at least as much as it did to Hugh Despenser's, and he repeated the avaricious and tyrannical mistakes of the previous favourite, and added a few of his own.

Thanks to Edward III's lack of vindictiveness, however, Roger's descendants thrived in the later fourteenth century. His grandson Roger was restored to the earldom of March in 1354, his great-grandson Edmund married Edward III's granddaughter Philippa of Clarence, and his great-great-grandson Roger was heir to the throne of England in the late 1390s.

In memoriam: Roger Mortimer, 1287-1330, usurper of a king and lover of a queen, de facto king of England, died on this day 676 years ago.

24 November, 2006

Entrails and Emasculation

[As a matter of interest, Hugh was the fourth cousin twice removed of Edward II, the fifth cousin of Queen Isabella, the third cousin once removed of Roger Mortimer and his (Hugh's) wife Eleanor, and the second cousin of Mortimer's wife Joan de Geneville.]

Today marks the 680th anniversary of Hugh's hideous execution. On 16 November 1326, he and Edward II were captured in South Wales by Henry of Lancaster - Edward's first cousin and Hugh's brother-in-law (Henry's late wife Maud Chaworth was Hugh's elder half-sister). There's some dispute about where Hugh and Edward were when they were taken - possibly at Neath Abbey, or in open countryside near Llantrisant, supposedly during a terrific storm.

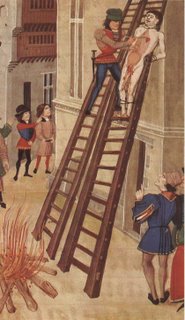

Hugh's execution, from a fifteenth-century manuscript of Froissart's chronicles. Is that really his penis hanging to his knees?? No wonder Edward liked him so much.

Below, the Despenser arms.

Edward II was taken to Kenilworth and treated with all respect, as befitted the king. Hugh, along with Robert Baldock, Archdeacon of Middlesex and Treasurer of England, and Simon of Reading, Hugh's marshal, were placed in the care of Thomas Wake, supporter of Roger Mortimer and Isabella. (Baldock, a cleric, was placed in the not-so-tender care of Adam Orleton, Bishop of Hereford, and died 'horribly abused' in Newgate prison a few months later.) They were taken to Hereford, where Mortimer and Isabella were waiting for them.

Thomas Wake was in fact Hugh's nephew by marriage. He was twenty-nine in 1326, born in May 1297, and extremely well-connected. He was Roger Mortimer's first cousin - their mothers were sisters - and his sister Margaret was married to Edward II's half-brother the earl of Kent. (She was the mother of Joan 'the Fair Maid of Kent' and the grandmother of Richard II). In 1316, Edward II tried to arrange the marriage of the nineteen-year-old Wake to Piers Gaveston's four-year-old daughter Joan, but Wake rejected the alliance, for which he had to pay a huge fine of 1000 marks, and instead married Blanche of Lancaster. Born in about 1302, she was the eldest child of Henry of Lancaster and Maud Chaworth. Wake, unsurprisingly, supported his cousin Mortimer and father-in-law in 1326. (In 1328/29 he turned against Mortimer, and was forced to flee the country.)

Wake did his best to make Hugh's journey as humiliating as possible. He was tied onto the meanest horse that could be found, and forced to wear a tabard bearing his coat of arms reversed. He was led through towns and villages to be made a public laughing stock; drums and trumpets marked the people's joy at the downfall of the hated favourite and tyrant. All kinds of rubbish and filth were thrown at him.

Isabella wanted Hugh to be executed in London. However, in an attempt to kill himself, Hugh was refusing to eat and drink anything, and she was afraid that he might be able to starve to death before his arrival in the capital. This suggests that he was under very close guard to ensure that he didn’t cheat Mortimer and Isabella of their revenge on him. Therefore, the execution took place in Hereford eight days after his capture. (Is it possible that, even in a climate as damp as Britain's in November, that a man could live for eight days with no water at all?)

On his arrival, a crown of nettles was placed on Hugh's head and Biblical verses were written, or carved, into his skin. On his shoulders, a verse from the Magnificat: 'He has put down the mighty from their seat and hath exalted the humble.' On his chest, verses from Psalm 52, beginning 'Why do you boast in mischief, o mighty man?' (Four years and five days later, the same verse was read out to Roger Mortimer at his own execution.)

Illustration from a fifteenth-century manuscript, showing Isabella, Roger Mortimer and the future Edward III at Hereford. Hugh's execution can be seen in the background - he's lying on a table.

His trial took place in the main square of Hereford, in the presence of Queen Isabella and her son, who had turned fourteen a few days earlier, Edward II's half-brother Kent, Roger Mortimer, and countless supporters. As had happened at the trial of Thomas of Lancaster in 1322, Hugh was not permitted to speak in his defence (though he was probably so weak from lack of sustenance that it's doubtful he could have defended himself anyway). The list of charges against him was read out by Sir William Trussell, a supporter of Thomas of Lancaster who had been forced to flee the country in 1322. This list of charges still survives; some of them are true, some a little bit true, some utterly ridiculous.

The oddest charge is that Hugh had Lady Baret tortured, by having her limbs broken, until she went insane. As far as I know, this is the only reference to the crime, and it's not even known for sure who Lady Baret was. It does seem strange that nobody else mentions a noblewoman being tortured, or that neither she nor her family presented petitions in Edward III's reign. On the other hand, the charge is surely too specific to have been plucked out of thin air.

Simon of Reading was accused of 'insulting the queen', a nicely vague but convenient charge, which obviously deserved to be punished with the horrors of the full traitor's death. It's hard to avoid the conclusion that his real crime was loyalty to Hugh, as he's a totally obscure figure who doesn't appear to have taken part in any of Hugh's schemes, nor shared Hugh's power.

Trussell read out the verdict:

Hugh, you have been judged a traitor, since you have threatened all the good people of the realm, great and small, rich and poor, and by common assent you are also a thief. As a thief you will hang, as a traitor you will be drawn and quartered, and your quarters will be sent throughout the realm. And because you prevailed upon our lord the king, and by common assent you returned to the court without warrant, you will be beheaded. And because you were always disloyal and procured discord between the king and our very honourable lady the queen, and between other people of the realm, you will be disembowelled, and your entrails will be burnt.

Go to meet your fate, traitor, tyrant, renegade! Go to receive your own justice, traitor, evil man, criminal!

Hugh was roped to four horses - not the usual two - and dragged through the streets to the castle. He was hanged and half-strangled on a gallows fifty feet high, then lowered and tied onto a ladder. The executioner climbed an adjacent ladder and cut off his penis and testicles (according to several chroniclers; this was not part of his sentence), and cut out his entrails and his heart. All these parts were flung onto a fire below him. Finally, his body was lowered to the ground to be beheaded.

Apparently, Hugh ‘suffered with great patience, begging forgiveness from the bystanders.’ According to Paul Doherty, Mortimer and Isabella feasted and celebrated while watching. They must have had incredibly strong stomachs. There were hundreds, maybe even thousands, of people present; the din of their triumphant shouting and cheering was tremendous. Simon of Reading was hanged ten feet below Hugh, as 'his guilt was less'. It's doubtful that many people present at his death had any idea who he was.

Hugh’s head was parboiled in salt water and placed on London Bridge, while his body was cut into four and displayed on the city walls of York, Carlisle, Bristol and Dover - almost the four corners of England.

After Roger Mortimer’s execution four years later, Edward III gave permission for Hugh’s family to retrieve his remains and bury him. His tomb at Tewkesbury Abbey still exists (you can see my photo of it in a previous post).

It's hard to imagine that many people grieved for Hugh, at least outside his family. Edward II certainly did, but he was in no position to avenge his friend's death - which he would have done, mercilessly, if he'd been able to.

Hugh's widow Eleanor de Clare was imprisoned in the Tower of London. Three of Hugh's five daughters, Joan, Eleanor and Margaret, were forcibly veiled as nuns, by Queen Isabella's direct order, about five weeks after his death. The eldest of the three was about ten. His other two daughters were spared, Isabel because she was already married, and Elizabeth because she was a baby, or possibly still in utero. Elizabeth le Despenser later married Maurice, Lord Berkeley, son of Edward II's jailor - and grandson of Roger Mortimer. After the downfall of Mortimer and Isabella, Hugh's four sons, especially the eldest (also named Hugh, inevitably) began the long but ultimately successful process of restoring the Despenser family fortunes and reputation. Hugh's great-grandson Thomas Despenser was created earl of Gloucester in 1397, and married Constance of York - great-granddaughter of Edward II and Isabella.

In memoriam: Hugh le Despenser the Younger, executed exactly 680 years ago. Not A Very Nice Guy, but an interesting one. ;) I'll be toasting him with a glass of bubbly later!

15 November, 2006

Edward II in custody 1327: part two, escapes

The reasons for the Dunheveds' great loyalty to Edward II are uncertain (see the post below this one for some biographical details of them). Edward seems to have been the kind of man who repelled many, or most, people with his odd and unkingly behaviour, but in a very few people, he inspired intense loyalty and love. The gang itself was small, but Alison Weir points out that 'there must have been... a network of conspirators throughout the south-west' supporting them. Supposedly, some of the 'great ones of the land' were supporting them - who, is uncertain.

One of these conspirators was Donald, earl of Mar, nephew of King Robert Bruce. Donald was born around 1300, son of Gratney, earl of Mar and Robert Bruce's sister Christina. He was taken to England as a hostage in 1306 with many members of his family, though Edward I ordered that he didn't have to be held in chains, because of his tender age. At some point, he ended up in Edward II's household, where he grew so devoted to the king that he refused to return to Scotland after Edward was forced to release all the Scottish hostages in 1314. Donald took part in Edward's campaign against the Marchers in 1321/22, and was at Bristol with the elder Despenser in October 1326. He managed to flee the city before Isabella and Mortimer took it, and returned to Scotland. He was implicated in the earl of Kent's conspiracy against Isabella and Mortimer in 1330, and was in the Welsh marches not far from Berkeley in June 1327, trying to rescue Edward.

What very few people realise, and what is truly fascinating, is that the Dunheved brothers succeeded in freeing the ex-king Edward II from Berkeley Castle in the summer of 1327. The exact details are unclear - 'shrouded in secrecy', you might say - but that Edward was temporarily free is certain. Somehow, members of the organised and extremely competent Dunheved gang, presumably hiding out in the numerous woods in the vicinity, gained entry to Berkeley Castle in June. Paul Doherty remarks that building work was being carried out on the castle at this time, and that perhaps members of the gang infiltrated the group of workmen. Alternatively, one man may have entered the castle dressed as a priest (as some of the gang were). Once one or several men were in, they could open a postern gate for the others. The looted and ransacked the castle, overcame Edward's guards, and fled outside with Sir Edward of Caernarvon, as he was now known.

The evidence for this extraordinary capture comes from a contemporary letter, written on 27 July 1327 at Berkeley Castle and addressed to the Chancellor, John de Hothum. The author was either John Walwayn, a royal clerk presumably investigating the affair, or Lord Thomas Berkeley himself. The author states that the Dunheved gang had been indicted for 'abducting the father of our lord the King [Edward III] out of our guard, and feloniously plundering the said castle'. Twenty-one men are named. On 1 August, Thomas Berkeley was given special powers to hunt down these men. By 20 August, one of them, William Aylmer, had been arrested at Oxford. Doherty speculates that Aylmer turned King's evidence and betrayed his former friends, as all evidence against him was quashed and he was released. Most of the other gang members were captured. The priests and friars were - illegally - not given benefit of clergy, as they should have been; Isabella and Mortimer had no time for such niceties. Most of the men just disappeared. There's some dispute about the fate of the Dunheveds themselves - Thomas, the friar and Edward's confessor, apparently died in Newgate prison, and Stephen evidently managed to evade capture. It seems likely that he joined the conspiracy of Edward's half-brother, Edmund earl of Kent, in 1330.

Doherty draws attention to an interesting murder case of 1329, before King's Bench. A man named Gregory Foriz was accused of murder; William Aylmer was named as one of his associates, and Henry earl of Lancaster (see my previous post) stood as Foriz's guarantor. This connection possibly points to a deeper conspiracy, involving Lancaster - the greatest magnate in England and a man starting to exercise profound misgivings about the regime of Isabella and Mortimer. He would rebel against them in late 1328.

There's no direct evidence that Edward was ever recaptured. However, as Weir points out, the letter of 27 July makes no reference to capturing Edward, only the men who'd freed him, so presumably he was already back at Berkeley. On the other hand, would Walwayn or Berkeley have dared to put down in writing that Edward was still at liberty? Obviously, Roger Mortimer and Queen Isabella couldn't afford to broadcast the fact that the ex-king was at large.

To judge by indirect evidence, however, it seems that Edward was back at Berkeley by early September (unfortunately...;) Around this time, yet another plot was hatched to free him from Berkeley, by a Welsh lord named Rhys ap Gruffydd, yet another man who would support Kent in 1330. Edward was very popular in Wales, and Mortimer was detested, thanks to his empire-building. Rhys and his uncle had long been loyal supporters of Edward, and Rhys fled to Scotland around the time of Edward's deposition. His plot was discovered on 7 September, when he was betrayed to William Shalford, Roger Mortimer's lieutenant in South Wales. Shalford wrote to Mortimer on 14 September that 'if the Lord Edward was freed, that Lord Roger Mortimer and all his people would die a terrible death by force and be utterly destroyed, on account of which Shalford counselled the said Roger that he ordain a remedy in such a way that no one in England or Wales would think of effecting such deliverance'. [Not the original letter, but from a court case of 1331 when Shalford was accused of being an accessory to Edward's murder.]

On the night of 23 September, nine days after Shalford's letter, Edward III was informed of his father's death...

10 November, 2006

Edward II in custody 1327: part one

Henry was King Edward's cousin, the son of Edward I's brother Edmund Crouchback, earl of Lancaster (1245-1296). He was born in about 1281 and was the younger brother of Earl Thomas of Lancaster, Edward II's most implacable enemy, beheaded in 1322. Through his elder half-sister Jeanne, Queen of France and Navarre, he was also the uncle of Queen Isabella.

Henry, arguably the only person to emerge from the period 1327-30 with any credit, treated the fallen king with respect and honour. In January, Edward was either forcibly deposed, or abdicated voluntarily - it's still not entirely clear which - leaving the new rulers of England with the thorny problem of what to do with the ex-king. Many people were uneasy with the situation of the king being in prison, but if Edward were released, he could revoke his deposition and reinstate himself. The death of Mortimer, and probably Isabella too, would certainly be the result - they had executed the Despensers, and Edward could be vindictive and merciless in revenge. Also, Henry - although an ally of the couple and Isabella's uncle - was a political danger. To ensure his support, Isabella and Mortimer had promised him his brother's earldom of Lancaster, but the huge lands and revenues of the earldom gave him great power, and his brother Thomas had used that power to constantly disagree with and thwart Edward. Although Isabella and Mortimer had needed Henry's support during their revolution, they now had to neutralise him. Custody of the king gave him enormous leverage over them - he could threaten them with Edward's restoration any time he was dissatisfied, and they didn't want Henry to wield the kind of disruptive power his brother had.

To add to their problems, a group of Edward's supporters were plotting to free him from Kenilworth in March 1327. The gang's leaders were the Dunheved (or Dunhead) brothers: Thomas, a Dominican friar and King Edward's confessor, and Stephen, Lord of Dunchurch in Warwickshire. There were contemporary rumours that Edward had sent Thomas to the Pope to secure a divorce from Isabella. While there's no direct evidence of this, it's quite plausible.

The other conspirators were: two men named William Aylmer (one the parson of Donnington Church), William Russell, Thomas Haye, Edmund Gascelyn, William Hull and John Morton. There was a flurry of writs and orders for their arrest, issued by an alarmed Mortimer and Isabella who had numerous other problems to contend with also, but the gang managed to evade capture - and were to cause many more headaches for Mortimer and Isabella later in the year.

In late March 1327, the former Edward II was removed from Kenilworth and sent to Berkeley Castle, in Gloucestershire. It's not clear if Henry of Lancaster agreed to Edward's removal - 'washed his hands of him', in Paul Doherty's words - or if it was forced on him. According to Ian Mortimer's recent biography of Edward III, Roger Mortimer supervised Edward's removal himself, and Henry was furious, though Doherty and Alison Weir claim that Henry was keen to rid himself of the huge responsibility for Edward.

The Lord of Berkeley was Thomas, who was born about 1293/97, and married Roger Mortimer's eldest daughter Margaret in 1319. He and his father Maurice were imprisoned by Edward in early 1322, during Edward's successful campaign against the earl of Lancaster and the Marcher lords, and Maurice died in prison at Wallingford Castle in 1326. Thomas, therefore, had every reason to detest the former king, and given that his father-in-law was now the main power in England, every reason to remain loyal to him. Berkeley had the advantage of being far away from Scotland, where many of Edward's allies were, and also, the Dunheveds were strong in the vicinity of Kenilworth. The disadvantage of Berkeley was its proximity to Wales, where Edward had more friends, but on the plus side, it was remote and secure. Edward arrived there by 6 April 1327 at the latest. Thomas Berkeley and his brother-in-law Sir John Maltravers - Edward's joint jailor - were awarded the princely sum of five pounds per day for the former king's upkeep.

The chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker, several decades later, gives the familiar story that Edward was mistreated at Berkeley, humiliated, half-starved, and incarcerated in a cell above animal carcasses, in the hope that the stench would kill him. However, it's also possible that Edward was treated reasonably well. The records show that he received delicacies such as capons and wine, though it may be that his guards stole them. While it seems highly unlikely that he was treated as an honoured guest, the stories of his incarceration above rotting animal carcasses may be exaggerated. It's difficult to know for sure. One thing that is definite is that Edward never saw his wife or his children again.

In part two, shortly, I'll look at the little-known story of Edward's secret release from Berkeley in the summer of 1327.

29 October, 2006

Edward II Novel of the Week (7): 'The She-Wolf' by Pamela Bennetts

Most unusually for an Edward II novel, The She-Wolf opens in 1325, shortly before Edward sends Isabella to France to negotiate with her brother Charles IV over the Gascon situation. It closes just after Edward III's successful coup against his mother and Roger Mortimer in late 1330.

Pamela Bennetts has an excellent understanding of the politics and general comings and goings of Edward II's reign, although sometimes she uses infodumps in the narrative to get the point across. Also, the late opening of the novel requires a lot of flashbacks in the first chapter to see Piers Gaveston, and the fact that falling in love with men is a pattern of Edward's behaviour. However, these are minor criticisms; the dialogue and characterisation are uniformly excellent.

I've never read another Edward II novel where Queen Isabella is so unsympathetic - the title is highly appropriate! Much of The She-Wolf is seen through the eyes of Isabella's attendants, who slowly come to realise that the sweet, suffering woman they adore is in fact - not to put too fine a point on it - a complete bitch, calculating, manipulative and so full of anger and hatred that she's almost abnormal. Even Roger Mortimer, who's also described as almost insane with ambition and bitterness, is frightened at what he unleashes. Isabella watches the execution of the younger Despenser and regrets that he doesn't last longer and suffer more. She is completely indifferent to her husband's murder, and the execution of her brother-in-law Kent. And yet, the reader can't help but feel sorry for her, at least in the earlier part of the novel. She genuinely yearned for Edward when they first married, and felt unclean at the thought of his relationship with Gaveston. Her frustrated love is warped and twisted until she feels nothing but hatred and contempt for her husband, and her relationship with Mortimer has nothing sweet or tender about it - it's based on lust and control.

Mortimer and Isabella are masters of propaganda here - even Isabella's reunion with her younger children in Bristol in October 1326 is stage-managed in front of a crowd to increase their sympathy for a woman deprived of her children by her heartless husband, and Mortimer only pretends to care that his wife and own children have been imprisoned, because it gives him a stronger reason to take revenge on the king and Despenser. Even Mortimer doesn't trust Isabella completely.

Edward II himself is reasonably sympathetic. At the start of the novel, he and Isabella utterly detest one another - they speak honeyed words to each other in public, while wanting to spit at and slap each other. It's a lovely portrayal of a marriage that's gone as wrong as a marriage possibly could. Although Isabella chooses to believe otherwise, and spreads vicious rumours about them, he and Hugh Despenser are not lovers here. Edward loves Despenser, but only because Despenser supports him and takes on the burden of ruling, which Edward doesn't want.

Edward III, after his father's murder - by the usual method - realises that the only way he will survive and overcome Mortimer is to bide his time, and copy his mother in hiding his true feelings and his true nature, and pretending to be meek and biddable.

In conclusion, this short novel is well worth a read, with excellent characterisation and genuine suspense near the end, as the reader wonders whether Edward III will be successful in his coup against Isabella and Mortimer - even while knowing that, historically, he was. But it's definitely not a novel for anyone who believes the recently popular 'Isabella has been unfairly maligned by history' theory!

21 October, 2006

Novels, names and Nottingham (and a tomb)

This is the tomb of Hugh le Despenser the younger, buried in Tewkesbury Abbey in late 1330 or early 1331, after the five parts of his body had been on public display around England for four years. The tomb was much mutilated in the sixteenth century, and used to contain forty statues. The coffin actually belongs to Abbot John Cotes, who died in 1347 - and who was probably the man who presided over Hugh's funeral. For some reason, his coffin was placed in the tomb in the seventeenth century. Despenser's remains are presumably underneath.

Barbara Green of the Yorkshire Robin Hood Society has left a long and fascinating comment on an old post, here. Many thanks for that, Barbara! She points out that, contrary to popular belief, the real Robin Hood most likely did not live in Richard I's reign, but in Edward II's. This has inspired me to follow up her references and read more about this. (Anyone watching the BBC's Robin Hood, by the way? I caught the first one during my holiday. One episode was more than enough, I think.)

Remember the romance novel Infamous, that I reviewed a while back? The sequel Notorious is due out next May, starring Jory de Warenne's daughter Brianna. According to this message board, the hero is Roger Mortimer's son....Wolf.

Words fail me.

A novel far superior to this one, I'm sure, is currently being written - one that takes place in 1330 and has the hero playing a role in Edward III's coup against Isabella and Roger Mortimer (yes, the one who fathered a son named Wolf. Allegedly.) I don't know the identity of the author, but you can see an extract of her work in progress here. She was also kind enough to leave some comments on the post below this one. Isabella, according to the author, is very much the 'She-Wolf' here - in my view, a welcome antidote to the fawning dissertations, biographies and novels featuring Isabella that are currently fashionable.

And finally, on the subject of Edward III's 1330 coup, Susan Higginbotham has written an excellent post on the subject. The 676th anniversary fell a couple of days ago (assuming my maths is correct; it's been a long week). Susan draws attention to Isabella and Mortimer's foolish behaviour during their regency. They'd invaded England supposedly to liberate the people from the tyranny of the Despenser regime, but proved themselves to be even greedier and less able to command the loyalty of their followers - something all too often conveniently ignored in recent works on Isabella.

15 October, 2006

Photos

The Three Kings pub in Hanley Castle, Worcestershire:

The church at Hanley Castle:

The 'Kneeling Knight' of Tewkesbury - Edward, Lord Despenser (1336-1375), grandson of Hugh the Younger and grandfather of Isabelle, below. His son Thomas was created earl of Gloucester in 1397 and beheaded in 1400, trying to put Richard II back on the throne. Edward was described by the chronicler Jean Froissart as the most handsome, the most courteous and the most honourable knight in England' (qualities he probably didn't inherit from his notorious grandfather ;)

The Despenser/Beauchamp chantry at Tewkesbury - paid for by Isabelle Despenser (1400-1439), great-great-granddaughter of Hugh the Younger and grandmother of Richard III's queen, Anne Neville. Isabelle had two husbands, both called Richard Beauchamp. ;) I love this photo because you can still see the colours of the chantry.

And for no other reason except that she's terribly cute, here's my mum's dog, Tara. ;)

More photos

Windows in the choir of Tewkesbury Abbey, paid for by Eleanor de Clare:

Deerhurst church (founded before 804):

Odda's Chapel (consecrated 1056):

Hailes Abbey (founded 1246):

Sudeley Castle, from the back seat of the car:

Berkeley Castle:

EDIT: Blogger, or my PC, is having a snit - I'll post the remaining photos later, or tomorrow.

13 October, 2006

My Edward II Pilgrimage

I had a great time in Gloucestershire, visiting sites associated with Edward II. The thing I most wanted to see was Edward II's tomb, in Gloucester Cathedral - a magnificent canopied shrine described by the Cathedral as 'one of the great monuments of England'. The shrine is currently covered in scaffolding, as it's being restored, at a cost of £70,000, apparently. The Cathedral is planning a 'series of events to commemorate Edward II' in 2007 and 2008.

I found it really moving to be so close to Edward - I stood there for ages, until one of the men working on the tomb started giving me funny looks. The day before, we'd visited Berkeley Castle, where Edward was imprisoned in 1327 (and freed by some of his supporters - see the comments on this post). I'm afraid to say I found Berkeley rather disappointing, at least from an Edward point of view. Much of the castle is closed to visitors, and the guided tour barely mentions Edward and focuses instead on the later Berkeleys. You can see the cell where Edward was held, but not enter it - you can only peer through a rather narrow window. I was hoping to get some idea of how the Dunheveds might have entered the castle in 1327 and freed Edward, but unfortunately I couldn't picture it at all. Still, Berkeley is well worth a visit (it's closed till next April, however) for anyone interested in later periods of history. I did enjoy seeing the Great Hall, which was rebuilt by Thomas Berkeley, Edward's jailor, around 1340.

In the photo (left, above) Edward's cell is above the doorway on the right.

We also visited Tewkesbury Abbey, a superb building consecrated in 1121, bigger than fourteen English cathedrals, which was saved during the Dissolution when the townspeople bought it for £453. The Abbey is practically the mausoleum of the Despenser family - the notorious Hugh the Younger was buried here in late 1330, in five pieces, after Edward III finally gave permission for his rotting remains to be removed from London Bridge, York, Carlisle, Bristol and Dover four years after his execution. His wife Eleanor de Clare is here (burial place unfortunately unknown) as are numerous descendants of theirs.

Another site associated with the Despensers is Hanley Castle, in Worcestershire. Sadly there's absolutely nothing left of the castle itself - except the flat hill where it once existed - but Hanley Castle, the village, is very pretty with a lovely old church and a school founded in 1326. Edward II and Queen Isabella were guests of Hugh Despenser here in January 1324, and Eleanor de Clare was abducted from Hanley by her second husband, William la Zouche, in early 1329.

We also took the opportunity to visit other historical sites in Gloucestershire and Worcestershire. Evesham is the site of a battle of 1265, where Edward II's father defeated Simon de Montfort, earl of Leicester - his uncle by marriage. Roger Mortimer - grandfather of Edward II's Roger Mortimer - sent de Montfort's head to his wife as a present! Worcester Cathedral contains the tomb of Edward II's great-grandfather King John (died 1216) as well as the chantry of Prince Arthur, elder brother of Henry VIII. The village of Deerhurst, a mile or so from where we were staying, contains two pre-Conquest buildings, astonishingly enough: Odda's Chapel, of 1056, and the Church of St Mary, which dates back to before 804. We didn't go in, but saw Sudeley Castle, former home of Henry VIII's last wife Katherine Parr, and spent a morning in the driving rain looking around Hailes Abbey - founded in 1246 by Henry III's brother Richard of Cornwall. Hailes was a very important place of pilgrimage in the Middle Ages.

All in all, I had a great holiday in a lovely, really interesting part of England!

26 September, 2006

Blog Hiatus, and Queen of Shadows

If you haven't read the comments on the last post, please do so - Carla and I had a fascinating discussion going on. When I get back, I'll write some more posts on the theory that Edward II wasn't murdered at all, and on his escape from Berkeley Castle in the summer of 1327.

Before I go, here's a review of Edith Felber's Queen of Shadows, released 7 November, from Amazon.com:

***

Isabella, the French princess at the center of Felber's deftly plotted historical, matures from a 12-year-old bride of Edward II of England to a clever conspirator driven by a thirst for power. Not so secretly gay and viewed as weak, Edward is ordered by Parliament to share his throne with the Earl of Winchester, whose son, Hugh, attracts Edward's attention. Isabella chafes at having to share the throne, particularly with Hugh, who proves to be a rapacious presence. One of Isabella's ladies-in-waiting, Gwenith of the Marches, secretly plans revenge against Edward for his killing of her family, but her dedication to Isabella complicates her mission. After being introduced by Gwenith, Isabella takes condemned nobleman Roger Mortimer, imprisoned in London Tower, as a lover and with him plots a coup that unseats Edward and positions Isabella's son Edward as king. But Roger is shiftier than he initially appears, and allegiances, as ever, are up for grabs. The book is filled with strong-willed characters, though Edward's homosexuality is clumsily handled. Felber, who has written many historical romances as Edith Layton, delivers what fans of the genre want.

***

A big, resounding 'hmmmm....'. The bit about Edward being ordered by Parliament to share his throne with Winchester (Hugh Despenser the Elder) is complete nonsense, and the bit about Isabella and Roger Mortimer being introduced by Gwenith makes me giggle ("Your grace, this is Lord Mortimer, whom you've been seeing around court for the last few years. Lord Mortimer, this is the queen of England." Mortimer: "Seriously??") Not sure about the 'clumsily handled homosexuality' either. I hope Felber hasn't made Edward into a flaming queen, or there may be a book/wall interface. And 'London Tower'?? I hope that's Publishers Weekly's error, not Felber's.

Still, I'm looking forward to it, although I have a feeling I'm not going to like it very much...but only time will tell.

21 September, 2006

Edward II's Death (?)

After Edward II's forced abdication in January 1327, he was first 'imprisoned' at Kenilworth Castle, under the care of his cousin Henry of Lancaster, who treated him with respect and honour. In April, he was transferred to Berkeley Castle, Gloucestershire, where his jailor was Thomas, Lord Berkeley - the son-in-law of Roger Mortimer. Berkeley had been imprisoned for several years by Edward, and his father had died during his own imprisonment, so he had little reason to like the king.

The chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker, written about thirty years later, mentions Edward's ill-treatment. He was held in a cell above the rotting corpses of animals, in an attempt to kill him indirectly. But Edward was extremely strong, fit and healthy, and survived the treatment, until on the night of 21 September 1327, he was held down and a red-hot poker pushed into his anus through a drenching-horn. His screams could be heard for miles around.

This has become the standard narrative of Edward's death, but there are problems with taking it at face value. Baker hated Queen Isabella (the 'iron virago') and was constructing a narrative of 'Edward as martyr'. The chronicles written shortly after Edward's death (Anonimalle Chronicle, a shorter continuation of the Brut, Lichfield Chronicle, Adam Murimith) variously state only that he died (with no explanation given), that he died of a 'grief-induced illness', or that he was strangled or suffocated. The official pronouncement of Edward's death, in September 1327, claimed that he died of 'natural causes'. It wasn't described as murder until November 1330, when Roger Mortimer was accused of 'having [Edward] murdered at Berkeley' during his show trial.

The earliest reference to the 'red-hot poker' method is found in a longer continuation of the Brut, written in the 1330s. However, many other fourteenth-century chronicles do not repeat this allegation. None of the men who killed Edward - for the purposes of this post, I'm assuming that he really was murdered in 1327 - ever spoke about it publicly. Therefore, we're dealing with rumour and hearsay, how the chroniclers thought he'd been murdered.

Admittedly, I find it very hard to view Edward's death objectively - I'm very fond of him, and would rather believe that he didn't die in such a vile way. However, the red-hot poker story does seem implausible. The idea was to kill him in such a fashion that no marks of violence would be visible on his body. However, why then kill him in such an agonising fashion that his screams could be heard for miles around? Why torture him, so that his (dead) face wore an expression of agony, if you were trying to pretend that his death was natural? Surely strangling or smothering, or even poison, would have been more effective. These methods would also have left physical traces on Edward's body, but if his eyes were closed and his body covered up, they would have been missed by the people viewing his body.

Here are some other ideas on the story:

- Mary Saaler, in her 1997 biography of Edward II, quotes Adam Murimith's comment that Edward was killed per cautelam, by a trick, and wonders if this phrase became corrupted to per cauterium, a branding-iron.

- Pierre Chaplais and Ian Mortimer have commented on the death of King Edmund Ironside in 1016, said to have been murdered in a similar way to Edward, while sitting on the privy. The story was often repeated in thirteeth-century chronicles.

- And finally, Edward's brother-in-law the earl of Hereford was killed at the Battle of Boroughbridge in 1322 when he was skewered through the anus by a spear pushed up through the bridge.

It's my belief that the grotesque 'anal rape' narrative of Edward's death (Dr Ian Mortimer's phrase) is nothing more than a reflection of the popular belief that Edward was the passive partner in sexual acts with men, and that this means of death represented Edward receiving his 'just desserts'. The deaths of the earl of Hereford and Edmund Ironside may have provided the inspiration for this.

Similarly, the castration (or emasculation) of Edward's favourite, the younger Despenser, in November 1326, was said by the chronicler Jean Froissart to be a punishment for his sexual relations with Edward. Whether this is true or not is impossible to say, but I think the narratives of both men's deaths reflect the widespread belief that they had sexual relations and were punished for them. Often, a story that begins as a joke or a rumour takes on the aura of 'truth' - such as the death of Edward's descendant George, Duke of Clarence, who died in the Tower of London in 1478. He is supposed to have drowned in a 'butt of malmsey'. It's difficult to ascertain whether this is the truth, or merely reflects his reputation as a drunkard.

Perhaps the story also represents a general human willingness to believe the most gruesome story - after all, being murdered with a red-hot piece of metal in the anus is far more 'interesting' than being smothered. And perhaps we shouldn't discount the early account of Edward's death from 'grief-induced illness', the accusation against Mortimer notwithstanding. At first sight it's not very plausible, but it is possible - given that Edward had lost his throne, his friends were dead, his family had turned against him, and he never saw his children again. If Edward was murdered in 1327, I'm far more inclined to believe that he was suffocated or strangled. He was a strong man and would have resisted, but of course he could have been murdered while he was asleep, or drugged.

But a far more fascinating question is - was Edward really murdered in 1327? Some modern historians incline to the view that he wasn't - which will be the subject of a further post shortly!

Until then, I'm going to raise a glass to King Edward II, who may or may not have died exactly 679 years ago. Cheers, Your Grace!

15 September, 2006

One Letter Makes All The Difference

Lard of Misrule: Piers Gaveston's problems with overeating and the fury it engenders in Edward II's barons. (Lord of Misrule, Eve Trevaskis)

King's Wade: Bored with rowing and swimming, Edward II constructs a new water feature at his favourite manor of Langley. (King's Wake, Eve Travaskis)

The Traitor's Wire: Hugh Despenser becomes a successful pirate with the aid of a length of cable, and wonders how it could help him improve his extortion skills. (The Traitor's Wife, Susan Higginbotham)

Harlow Queen: The famous actress learns that she was Queen Isabella in a previous life. (Harlot Queen, Hilda Lewis)

The Tournament of Brood: The women of Edward II's court take part in an unusual competition to see who is the most desperate for a baby. (The Tournament of Blood, Michael Jecks)

Isabel the Pair: Isabel(la) is shocked to learn that she has an identical twin sister with the same name. (Isabel the Fair, Margaret Campbell Barnes)

The Love Knit: Isabella gets out her needles to make Roger Mortimer warm cardigans and mittens, in order to prove her love for him. (The Love Knot, Vanessa Alexander)

The Dollies of the King: Edward II tries desperately to keep his large collection of dolls a secret. (The Follies of the King, Jean Plaidy)

The Zion of Mortimer: After escaping from the Tower, Roger travels to Jerusalem to drum up support for his anti-Edward platform. (The Lion of Mortimer, Juliet Dymoke)

The She-Golf of France: Fed-up with unisex sports, Isabella returns to France to play her favourite game on a women-only course. (The She-Wolf of France, Maurice Druon)

Death of a Ming: During a row with Edward, a furious Isabella throws a vase at him. (Death of a King, Paul Doherty)

The Bows of the Peacock: Edward tries to teach a bird how to genuflect before his royal majesty. (The Vows of the Peacock, Alice Walworth Graham)

The King is a Ditch: Edward II takes one of his favourite hobbies very seriously indeed. (The King is a Witch, Evelyn Eaton)

Hummer of the Scots: Edward I invades Scotland with the aim of providing all the inhabitants with an SUV. (Hammer of the Scots, Jean Plaidy)

09 September, 2006

Edward II's Maternal Family

Eleanor's mother was Jeanne de Dammartin, born circa 1216/20, Countess of Ponthieu and Montreuil in her own right. Jeanne had once been betrothed to Henry III, but he broke off the engagement in order to marry Eleanor of Provence. She married Fernando III, king of Castile and Leon, in 1237. Born circa 1200, Fernando united the kingdoms of Castile and Leon in 1231, and spent a large part of his reign fighting the Moors. His first marriage to Elisabeth of Hohenstaufen, cousin of Emperor Frederick II, produced ten children. On his death in 1252, Fernando was succeeded by his son Alfonso X, born 1221, reigned 1252-1284. He was known as 'El Sabio', 'The Wise' or 'The Learned', and was Edward II's half-uncle. Fernando III was canonised in 1671 (I really like the fact that Edward II was the grandson of a saint!)

The marriage of Fernando III and Jeanne de Dammartin produced one daughter, Eleanor, two sons who died in early childhood, and two other sons who both died in 1269. After she was widowed, Jeanne returned to her native Ponthieu, where she died in 1279. Her only surviving child Queen Eleanor inherited Ponthieu and Montreuil, which eventually passed to her son, the future Edward II, on her death in 1290. As Edward was only six years old then, the lands were adminstered for him by his uncle Edmund of Lancaster. Edward granted the revenues of Ponthieu and Montreuil to Isabella three months after their wedding in 1308. The lands passed to the French crown during the Hundred Years War.