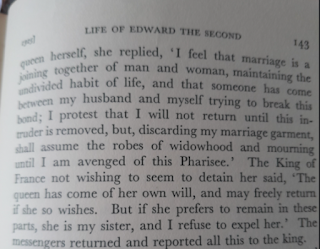

In late October 1325 or thereabouts, Edward II's queen Isabella made a speech at her brother Charles IV's court in Paris that appears in the Vita Edwardi Secundi, though nowhere else. Assuming that the Vita recorded Isabella's words correctly or approximately correctly - and bear in mind that the queen would have spoken in French, which the author of the Vita recorded in Latin, and which has been translated into modern English - this is the speech:

Paraphrasing the queen, what she said was: "There is a third person in my marriage who is trying to come between my husband and myself, and marriage is a very important institution to me but now I feel like a widow and am going to dress like one. I want my husband to send this Pharisee away so that I can return to him, and get my own back on this horrible person."

Her brother Charles IV, who evidently was present, responded: "My sister is always welcome to stay here with me if she wants, but if she wants to go back to England, that's fine too."

Modern writers often interpret this speech as Isabella openly admitting treason and saying "I hate my husband and am defying him and want to bring him down, because I'm in love with Roger Mortimer," and Charles IV saying he'll aid her rebellion because he also wants to bring down Edward II. And I go, wait, what? Oh, and for the avoidance of any doubt, because there are people who accuse me of being unfair to novelists when I discuss this on my social media, I'm not talking about fiction here. I'm talking about the way historians have interpreted Isabella's speech, in works of non-fiction, not novelists writing fiction. How novelists depict Isabella often makes me roll my eyes right out of my head but isn't a massive priority of mine, to be honest, but I do care a great deal about a distorted view of her and Edward II being presented in serious works of non-fiction as though it's certain fact.

On the face of it, this speech is Isabella offering Edward II an ultimatum: he must send the unnamed 'Pharisee' away from him so she can return to him and resume their marriage. Some months later in early February 1326, Isabella sent a letter to Walter Reynolds, archbishop of Canterbury, in which she reiterated her strong wish to return to Edward, but stated that she did not dare to do so because she was so frightened of Hugh Despenser, who was in complete control of her husband and his realm. She referred to Edward as "our very dear and very sweet lord and friend", nostre treschier et tresdouche seignur et amy, highly unconventional terms which reveal her great affection for her husband (conventional would have been simply "our very dear lord"). But somehow, modern writers often seem to feel that they know exactly what Isabella was really thinking all the time, as though they're connected to her telepathically, so they go "Aha! She was just pretending to want to go back to Edward and didn't really mean it, so she made up her fear of Hugh Despenser as a useful excuse to stay away from Edward and to remain in Roger Mortimer's arms!" As Michèle Schindler has so correctly pointed out to me, it's really odd that historians have invented all kinds of ways in which Isabella of France was supposedly a victim - the nonsense about her children being stolen from her in 1324, being abandoned by Edward in 1312 when she was pregnant, endlessly neglected by her cruel gay husband who gave her wedding gifts to his lover, and so on - but on the one occasion where Isabella outright stated that she was indeed a potential victim, because she was so frightened of Hugh Despenser and what he might do to her, it's dismissed as a self-serving lie.

Another important point that I've been thinking about for a while is, who was this 'Pharisee'? According to the Vita Edwardi Secundi, Queen Isabella swore to destroy Hugh Despenser around the same time that she made this speech (see paragraph below). As she used the word 'avenged' in her speech at the French court to describe what she wanted to do to the 'Pharisee' who had come between her and Edward, it does seem natural that she was referring to the same person. But was she? It's almost always been assumed, including by me, that it must have been Hugh, but the queen didn't name him, and furthermore, the meaning of Pharisee is 'a self-righteous or hypocritical person'. That really doesn't seem to fit Hugh at all. He was a ruthless, clever, scary, ambitious and manipulative person, but for all his faults I can't think of a time when he demonstrated hypocrisy or self-righteousness. He was always cheerfully open about his ambitions to be supremely rich and to own most of South Wales, and about the less than entirely legal and ethical methods he employed to achieve this.

Below, the Vita cites a letter which all the English bishops, on Edward II's command, sent to the queen in France sometime in late 1325. It makes clear that Isabella, in a speech or letter which does not now survive, had threatened to destroy Hugh Despenser with the aid of her brother Charles IV and other powerful Frenchmen. It might not be a coincidence that in November 1325, rumours spread that Hugh had been killed in Wales.

I have wondered, and discussed the possibility in my book Edward II's Nieces, the Clare Sisters: Powerful Pawns of the Crown, whether the person Queen Isabella meant by 'Pharisee' was not Hugh Despenser but his wife Eleanor de Clare, Edward's eldest niece. There's a curiously large amount of evidence that Edward and Eleanor had some kind of intimate, and incestuous, relationship in the last years of his reign. And as Eleanor had regularly attended Queen Isabella going back to at least 1311 and probably earlier, and the two women had spent considerable time together for many years, it perhaps makes sense that Isabella would call Eleanor a hypocritical person if she was being friendly to Isabella's face while having an affair with her husband behind her back.

One Continental chronicle* says that Edward II and Isabella met at some point after her invasion in September 1326 - the timing isn't clear but appears to be sometime after Hugh Despenser's execution on 24 November 1326 and his wife Eleanor's imprisonment at the Tower of London a few days earlier - and that Isabella fell to her knees and begged Edward to 'cool his anger' with her. The king, however, refused even to look at her, never mind talk to her or accept her apology. It's always taken for granted that it was Isabella who was in charge, who actively defied Edward and whose decision it was to end their marriage, while Edward just reacted passively to events as they unfolded and had no choice about his marriage coming to an end. In this reading, however, and if the chronicle bears any resemblance to reality, it was Edward who rejected Isabella, not the other way around.

[* Extrait d'une Chronique Anonyme intitulée Ancienne Chroniques de Flandre in Recueil des Historiens des Gaules et de France, ed. M.M. de Wailly, vol. 22, p. 425]

Maybe Isabella genuinely did want to go back to Edward without Hugh and Eleanor Despenser's constant and irritating presence, and maybe it really was Edward who rejected her rather than vice versa. After all, it would appear that he refused the ultimatum that she offered him in or around late October 1325, perhaps to her great shock, and several months later in February 1326, Isabella told the archbishop of Canterbury that she still wanted to go back to her husband but that nothing had changed. Again, this letter has often been interpreted as Isabella playing a game, pretending that she wanted to go back to Edward when of course she can't possibly have done, because she was deeply in love/lust with the most heterosexual and virile manly man who has ever existed and who was sooooo superior to the horrid same-sex attracted man she'd been forced to marry. It's odd really. I'm not sure I've ever seen so many people so keen to argue that a person meant something so entirely different from the words she actually spoke, and so keen to claim that this pious daughter of Holy Church glibly told porkies to the most important churchman in England for no better reason than she wanted to continue having hot, doubly adulterous sex. I suppose it's because the constant but erroneous assumption that Edward II and Isabella of France's marriage was nothing but a tragic awful disaster from start to finish makes it hard to imagine that, just maybe, Isabella really did want to go back to Edward. That she wanted to resume a marriage in which she had been happy for many years, without Hugh and Eleanor Despenser always being around.

Perhaps the invasion of September 1326 was aimed at removing Hugh Despenser from Edward II's side and executing him, as the barons had tried to do with Piers Gaveston on several occasions a few years earlier, rather than being intended to remove Edward himself from his throne. Events in the autumn and early winter of 1326, however, snowballed; Edward's support simply collapsed; and it became clear that he could not continue as king. But maybe Edward's downfall was never originally the intention of Isabella and her allies. We don't really know. Whatever anyone else tells you, these people who seem to think they can see into the heart and mind of a woman who lived 700 years ago, we genuinely do not know when Isabella and the others decided that Edward II must be made to abdicate his throne to his and Isabella's son. It might even have been as late as the festive season of 1326, when a big What On Earth Are We Going To Do About The King meeting took place at Wallingford Castle. It's also possible that Edward's downfall/abdication/assassination might have been kind of vaguely contemplated, at least as a concept, years earlier. We just don't know, and don't believe anyone who tells you that we do know, or who tells you with complete certainty that Isabella was repulsed by her husband and in love with Mortimer in 1326, because there is no way that we can know those things. We mustn't lose sight of the fact, either, that in 1326/27 a king of England had never been deposed or forced to abdicate before. How would Isabella and her allies even have conceived of the notion that they might be able to achieve this, years before it happened, and long before they and parliament painstakingly and painfully groped their way towards it? It's not as though they had a precedent to work with, or any way of knowing that deposing unsatisfactory English kings would later become reasonably common.

There often seems to be this idea that everything that happened was always bound to happen and couldn't possibly have happened in any other way, and that any particular event wasn't a result of chance, or of fairly arbitrary decisions and choices, but must always have been carefully planned, step by step. Every single thing that we know Isabella and Roger Mortimer did or said, therefore, has to be fitted into a scheme of their clever and super-secret years-long plan to bring down Isabella's husband. So Isabella can't just stay at the royal residence of the Tower of London for a few nights in early 1323 because that's what the king and queen often did when they were in the city, she has to be conspiring against Edward with Roger Mortimer in prison there and helping him plan his escape as the vital first step in her plan to unking her husband. She can't argue with Edward in late 1322, flounce off in a huff but then go back to him a bit later and try to make up because that's what couples often do, she has to be conspiring against Edward with Roger Mortimer and spying on her husband's movements for him. She can't genuinely mean in late 1325 and early 1326 that she misses her happy marriage and wants to go back to her husband but is too frightened of Hugh Despenser to do so, she has to be conspiring against Edward with Roger Mortimer because she's in love with him, and is obviously lying her socks off so that nobody realises what she's up to. Roger Mortimer can't escape from the Tower and flee to the Continent without any clear idea of what the heck he's going to do once he gets there, he has to spend every waking moment from 1322 to 1326 manoeuvring everyone and everything into position so that the forced abdication of Edward II he's planning can be achieved.

In this way of thinking, obviously it can't be the case that Isabella, Roger, the count of Hainault, the king of France, etc, react to events as they happen, or make decisions on the spur of the moment, or are taken by surprise by the outcome of things they've almost inadvertently set in motion. Somehow all of them have to be part of this massive Europe-wide conspiracy of powerful people who want to see the king of England dethroned, who plot with each other for years on end, and who are all incredibly cunning uber-Machiavellian types who spend years bringing about an English king's downfall for the first time in history without leaving the slightest trace of their machinations on written record. This is a result of looking at history backwards; knowing where people ended up and assuming they were always fated to end up there and had always planned to end up there, and is imposing a coherent narrative on events that at the time they were lived were simply random and chaotic. It forgets that the people themselves were living from day to day, and were making whatever choices and decisions seemed like a good idea at the time, and couldn't actually foretell the future. It's only with hindsight that we can look back at history and see that other English kings after Edward II lost their thrones - Richard II, Henry VI, Edward V, Charles I - and thereby assume that people alive in the 1320s had somehow gone through the same conceptual process that we have, to wit, that failed kings could be unkinged, and that this notion surely occurred to Isabella, Roger Mortimer and others as early as 1322/23.

It's only with hindsight that we can look at Roger Mortimer's escape from the Tower in August 1323 and see that, yes, it was an important step in the events that would bring down Edward II a few years later. Neither Roger nor anyone else knew that in 1323. It's only with hindsight that we can look at Queen Isabella departing for France in March 1325 and see that, yes, this was another important step in the events that would bring down Edward II. Isabella didn't know that in 1325. It's certainly possible that when she left, she had some idea in mind of using her stay in her homeland and the influence of her royal French brother to try to alter her currently unhappy circumstances. Frankly, however, suggesting that she knew she would return to England at the head of an army with the aim of removing her husband from his throne, and that she'd been plotting to do so for years with the mid-ranking baron she was in love with, strikes me as an absurdity. And you know what? Sometimes when a woman says how unhappy she is about a third person in her marriage, what she really means is that she's unhappy about a third person in her marriage.

10 comments:

Brilliant once again. I have very serious ideas about the Eleanora-situation and why that could have been the thing for Isabella. Ok, there was Hugh, whom Edward at some point had a crush or something BUT there was also Eleanor whom Edward really took a shine for. And Hugh being Hugh, it would not be completely outlandish for him to set up a secret tryst between the king and Eleanor, and once that happened he had the king by the balls almost literally. For Isabella the male favorites were usually just a thing her husband had, like a weird hobby or something like that, but to have a female lover with the backing of a very dangerous male favorite was something else. There could always be a son, yes born outside of marriage BUT still the son of the king, and that would put her own son's future in danger in many ways. I believe Isabella, who was a master politician and strategist herself, realized this danger and decided to remove herself from the danger zone at once and secure her son too. Once that was done she came up with the plan to remove Hugh and Eleanora from the scene by any means possible. So she needed an armed troop but could not raise an full army. But being The Queen she certainly knew how bitter and disappointed many barons were. If she could convince them that she was not leading a French invasion but just returned as the rightful Queen, they might bring their troops to the play and then she would have an army. In order to convince the barons she needed an Englishman to be the nominal leader of her mercenaries and he found one in Roger Mortimer who most likely was more than glad to assist the Queen and take his own revenge. Thus Isabella won the barons on her side and managed to bring down Hugh and Eleanora and on the same run her husband also who, being who he was, did not forgive her wife nor got back to the business of running his realm but instead behaved like a high scholl jock who has been trocked by a cheerleader.

Bravo - brilliant analysis of the most likely situation. I think people love a good conspiracy theory (just look at the ones today) without considering the immense amount of coordination, foresight, and collaboration between several parties that would have been required. You and Sami have, I think, hit the nail on the head about what most likely was going on - and everything developed organically from there. No great plan - just a desperate woman trying to save her marriage and adopted country from the ambition of one man (and possibly his wife).

Great article, as usual. Also, if Edward was able to annul his marriage to Isabella, would another son by another wife (assuming he could get a dispensation to marry Eleanor) become heir?

Esther

Thanks for the great comments, everyone! There was no way that in the 1320s that Edward would either have been able to annul his marriage to Isabella and there's no evidence he tried or wanted to, or that he would ever have received a dispensation to marry his own niece. I know some Spanish kings in later centuries did, but not in the fourteenth century.

I don't think Edward ever even toyed with the idea of annulment of his marriage. His son was going to be the king one day so he would not do anything to risk that. Plus I think he was more hurt by Isabella's trickery than hated her. Isabella had not only obeyed him but had also outsmarted him so there was a lot on the plate and Edward, neing who he was, was not going to eat that.

I'm relatively ignorant about this historical period, but (on a prosaic note) it would be interesting to know whether the Latin gives any clue as to the gender of the Pharisee. Assuming the Latin is an accurate reflection of the French, of course. I would be looking specifically at the words 'this person'.

Annette, I looked at the Latin and am not sure. 'Pharisee' is 'Phariseo' and 'someone' is 'individuam', but I'm not sure whether this necessarily signifies that the someone in question was male.

According to this, "Phariseo" would be either masculine or neuter in the dative (first/second declention) - hope that this link works

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Pharisaeus#Latin

Esther

Hi Kathryn -

Great insight, thank you! I won't pretend to help with the Latin as my four years of Latin study ended 42 years ago (!) other than it must be tough when one is translating from a translation.

I am convinced, rightfully or not, that Isabella was referring to Eleanor in her speech, if not directly, than indirectly. She (Eleanor) was the 'property' of her husband Hugh, as women had a lesser place in life at that time, and conceivably, any actions on her part could be interpreted as being the fault or responsibility of the husband. You have certainly uncovered enough evidence previously to demonstrate the relationship between Edward and Eleanor was something more than just close cousins. From the history of Hugh, it's not inconceivable that Hugh either, at the worst, manipulated the situation, or at the least, powerless to stop it, saw an opportunity (as Sami so succinctly observed) to have the king by the balls. Either way, Isabella, living in a male-dominated society speaking to powerful men, may have simply put it in terms they would understand, i.e., the husband is at fault and responsible for the actions of the wife.

As a scientist, we employ Occum's razor daily, and I believe you have utilized it beautifully here. Sometimes the simplest explanation is the correct one, and history has countless examples of unintended consequences - they were people, imperfect human beings with their own motivations, emotions and perceptions, and their actions (and inactions) were not born of the result some high-level Star Chamber discussions, but taken at the time to be the best they come up with at the time. Of course, they had discussions and discussed the possible consequences, but at no time did they really perceive the eventual outcome.

To boil it down to simple American terms, I feel it's a good example of, "Hold my beer", followed by, "Whoa...did NOT see that coming..." OK, maybe that a bit of an oversimplification, but you get the gist.

Esther, thank you for looking that up!

Chris, hi, lovely to see you again, and thanks for the great comment! It's also highly appropriate to cite the Razor of the Franciscan friar William Occam/Ockham, as he was almost exactly the same age as Edward II. ;-)

Post a Comment