Welcome to the site which examines the events, issues and personalities of Edward II's reign, 1307-1327.

29 November, 2006

The Execution of Roger Mortimer

Roger was born on the same day as Edward II, but three years later. Today marks the 676th anniversary of his execution at Tyburn, at the age of forty-three.

Roger was arrested in Nottingham Castle on 19 October 1330, in the hastily planned and executed seizure of power by the young Edward III, aged not quite eighteen. Apparently, Edward III wished to execute him immediately, but was persuaded by Henry, earl of Lancaster, to put Roger on trial before Parliament. Roger was first taken to Leicester, then imprisoned in the Tower of London until his trial on 26 November.

In keeping with several other so-called 'trials' of this time, of Thomas of Lancaster and the Despensers, Roger was not permitted to speak in his own defence when he was taken before Parliament at Westminster. In fact, he was gagged to make sure he couldn't speak. He was also bound, with ropes or chains. He was charged with fourteen crimes, including: the murder of Edward II; procuring the death of Edward's half-brother Kent; and taking royal power and using it to enrich himself, his children and his supporters.

The outcome of the 'trial' was never in doubt. Roger was found guilty of these crimes, and 'many others', by notoriety, that is, his crimes were 'notorious and known for their truth to you and all the realm'.

On 29 November 1330, Roger was taken from the Tower. He was forced to wear the black tunic he had worn to Edward II's funeral three years earlier, a pointed reference to his hypocrisy, and dragged behind two horses to Tyburn, where he would be hanged. His clothes were taken off him, so he died naked. Verses of the 52nd Psalm were read out loud to him - 'Why do you glory in mischief?' - and he was allowed to speak a few words to the crowd. He didn't mention Edward II, or Queen Isabella, but admitted his role in the judicial murder of the earl of Kent.

Roger was not, as is often stated, the first person to be executed at Tyburn (executions had taken place there for well over a century, since the 1190s), but he was the first nobleman to be hanged there. Tyburn was the execution site for common criminals, and hanging was the method used to dispatch them. Noblemen were usually beheaded. The Despensers were an exception, but in 1322 Edward II had commuted Thomas of Lancaster's sentence to be hanged, drawn and quartered to beheading, and in 1312 even Piers Gaveston was given the nobleman's death, because he was the earl of Gloucester's brother-in-law. The site and method chosen for Roger's execution were a deliberate attempt to treat him as a common criminal. At least Edward III spared him the full horrors of the traitor's death, and death came within a few minutes - a relief, as medieval hanging victims often took hours to die.

Roger's burial site is uncertain. He is stated to have been buried at the Grey Friars church in Shrewsbury, but a year after his death, his widow Joan de Geneville petitioned Edward III for his body to be removed to Wigmore, and it was the Franciscans of Coventry who were licensed to deliver it. Wherever his final resting place was, his tomb is now lost.

Unfortunately the story that, twenty-eight years later, Isabella chose to be buried at the Grey Friars in London because it was Roger's final resting place, is not true, though it's still often repeated today. It is possible, however, that Roger's body lay there for a while before his final burial, though this hardly seems sufficient reason for Isabella to have been buried there (her aunt Marguerite was also buried there, in 1318).

Roger Mortimer was a fascinating man who deserves to be much better known. He was intelligent, competent, and ruthless, and, in the end, proof of the adage that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Power went to his head at least as much as it did to Hugh Despenser's, and he repeated the avaricious and tyrannical mistakes of the previous favourite, and added a few of his own.

Thanks to Edward III's lack of vindictiveness, however, Roger's descendants thrived in the later fourteenth century. His grandson Roger was restored to the earldom of March in 1354, his great-grandson Edmund married Edward III's granddaughter Philippa of Clarence, and his great-great-grandson Roger was heir to the throne of England in the late 1390s.

In memoriam: Roger Mortimer, 1287-1330, usurper of a king and lover of a queen, de facto king of England, died on this day 676 years ago.

24 November, 2006

Entrails and Emasculation

[As a matter of interest, Hugh was the fourth cousin twice removed of Edward II, the fifth cousin of Queen Isabella, the third cousin once removed of Roger Mortimer and his (Hugh's) wife Eleanor, and the second cousin of Mortimer's wife Joan de Geneville.]

Today marks the 680th anniversary of Hugh's hideous execution. On 16 November 1326, he and Edward II were captured in South Wales by Henry of Lancaster - Edward's first cousin and Hugh's brother-in-law (Henry's late wife Maud Chaworth was Hugh's elder half-sister). There's some dispute about where Hugh and Edward were when they were taken - possibly at Neath Abbey, or in open countryside near Llantrisant, supposedly during a terrific storm.

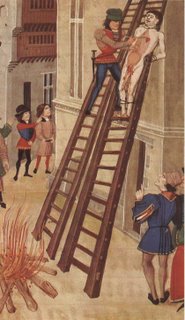

Hugh's execution, from a fifteenth-century manuscript of Froissart's chronicles. Is that really his penis hanging to his knees?? No wonder Edward liked him so much.

Below, the Despenser arms.

Edward II was taken to Kenilworth and treated with all respect, as befitted the king. Hugh, along with Robert Baldock, Archdeacon of Middlesex and Treasurer of England, and Simon of Reading, Hugh's marshal, were placed in the care of Thomas Wake, supporter of Roger Mortimer and Isabella. (Baldock, a cleric, was placed in the not-so-tender care of Adam Orleton, Bishop of Hereford, and died 'horribly abused' in Newgate prison a few months later.) They were taken to Hereford, where Mortimer and Isabella were waiting for them.

Thomas Wake was in fact Hugh's nephew by marriage. He was twenty-nine in 1326, born in May 1297, and extremely well-connected. He was Roger Mortimer's first cousin - their mothers were sisters - and his sister Margaret was married to Edward II's half-brother the earl of Kent. (She was the mother of Joan 'the Fair Maid of Kent' and the grandmother of Richard II). In 1316, Edward II tried to arrange the marriage of the nineteen-year-old Wake to Piers Gaveston's four-year-old daughter Joan, but Wake rejected the alliance, for which he had to pay a huge fine of 1000 marks, and instead married Blanche of Lancaster. Born in about 1302, she was the eldest child of Henry of Lancaster and Maud Chaworth. Wake, unsurprisingly, supported his cousin Mortimer and father-in-law in 1326. (In 1328/29 he turned against Mortimer, and was forced to flee the country.)

Wake did his best to make Hugh's journey as humiliating as possible. He was tied onto the meanest horse that could be found, and forced to wear a tabard bearing his coat of arms reversed. He was led through towns and villages to be made a public laughing stock; drums and trumpets marked the people's joy at the downfall of the hated favourite and tyrant. All kinds of rubbish and filth were thrown at him.

Isabella wanted Hugh to be executed in London. However, in an attempt to kill himself, Hugh was refusing to eat and drink anything, and she was afraid that he might be able to starve to death before his arrival in the capital. This suggests that he was under very close guard to ensure that he didn’t cheat Mortimer and Isabella of their revenge on him. Therefore, the execution took place in Hereford eight days after his capture. (Is it possible that, even in a climate as damp as Britain's in November, that a man could live for eight days with no water at all?)

On his arrival, a crown of nettles was placed on Hugh's head and Biblical verses were written, or carved, into his skin. On his shoulders, a verse from the Magnificat: 'He has put down the mighty from their seat and hath exalted the humble.' On his chest, verses from Psalm 52, beginning 'Why do you boast in mischief, o mighty man?' (Four years and five days later, the same verse was read out to Roger Mortimer at his own execution.)

Illustration from a fifteenth-century manuscript, showing Isabella, Roger Mortimer and the future Edward III at Hereford. Hugh's execution can be seen in the background - he's lying on a table.

His trial took place in the main square of Hereford, in the presence of Queen Isabella and her son, who had turned fourteen a few days earlier, Edward II's half-brother Kent, Roger Mortimer, and countless supporters. As had happened at the trial of Thomas of Lancaster in 1322, Hugh was not permitted to speak in his defence (though he was probably so weak from lack of sustenance that it's doubtful he could have defended himself anyway). The list of charges against him was read out by Sir William Trussell, a supporter of Thomas of Lancaster who had been forced to flee the country in 1322. This list of charges still survives; some of them are true, some a little bit true, some utterly ridiculous.

The oddest charge is that Hugh had Lady Baret tortured, by having her limbs broken, until she went insane. As far as I know, this is the only reference to the crime, and it's not even known for sure who Lady Baret was. It does seem strange that nobody else mentions a noblewoman being tortured, or that neither she nor her family presented petitions in Edward III's reign. On the other hand, the charge is surely too specific to have been plucked out of thin air.

Simon of Reading was accused of 'insulting the queen', a nicely vague but convenient charge, which obviously deserved to be punished with the horrors of the full traitor's death. It's hard to avoid the conclusion that his real crime was loyalty to Hugh, as he's a totally obscure figure who doesn't appear to have taken part in any of Hugh's schemes, nor shared Hugh's power.

Trussell read out the verdict:

Hugh, you have been judged a traitor, since you have threatened all the good people of the realm, great and small, rich and poor, and by common assent you are also a thief. As a thief you will hang, as a traitor you will be drawn and quartered, and your quarters will be sent throughout the realm. And because you prevailed upon our lord the king, and by common assent you returned to the court without warrant, you will be beheaded. And because you were always disloyal and procured discord between the king and our very honourable lady the queen, and between other people of the realm, you will be disembowelled, and your entrails will be burnt.

Go to meet your fate, traitor, tyrant, renegade! Go to receive your own justice, traitor, evil man, criminal!

Hugh was roped to four horses - not the usual two - and dragged through the streets to the castle. He was hanged and half-strangled on a gallows fifty feet high, then lowered and tied onto a ladder. The executioner climbed an adjacent ladder and cut off his penis and testicles (according to several chroniclers; this was not part of his sentence), and cut out his entrails and his heart. All these parts were flung onto a fire below him. Finally, his body was lowered to the ground to be beheaded.

Apparently, Hugh ‘suffered with great patience, begging forgiveness from the bystanders.’ According to Paul Doherty, Mortimer and Isabella feasted and celebrated while watching. They must have had incredibly strong stomachs. There were hundreds, maybe even thousands, of people present; the din of their triumphant shouting and cheering was tremendous. Simon of Reading was hanged ten feet below Hugh, as 'his guilt was less'. It's doubtful that many people present at his death had any idea who he was.

Hugh’s head was parboiled in salt water and placed on London Bridge, while his body was cut into four and displayed on the city walls of York, Carlisle, Bristol and Dover - almost the four corners of England.

After Roger Mortimer’s execution four years later, Edward III gave permission for Hugh’s family to retrieve his remains and bury him. His tomb at Tewkesbury Abbey still exists (you can see my photo of it in a previous post).

It's hard to imagine that many people grieved for Hugh, at least outside his family. Edward II certainly did, but he was in no position to avenge his friend's death - which he would have done, mercilessly, if he'd been able to.

Hugh's widow Eleanor de Clare was imprisoned in the Tower of London. Three of Hugh's five daughters, Joan, Eleanor and Margaret, were forcibly veiled as nuns, by Queen Isabella's direct order, about five weeks after his death. The eldest of the three was about ten. His other two daughters were spared, Isabel because she was already married, and Elizabeth because she was a baby, or possibly still in utero. Elizabeth le Despenser later married Maurice, Lord Berkeley, son of Edward II's jailor - and grandson of Roger Mortimer. After the downfall of Mortimer and Isabella, Hugh's four sons, especially the eldest (also named Hugh, inevitably) began the long but ultimately successful process of restoring the Despenser family fortunes and reputation. Hugh's great-grandson Thomas Despenser was created earl of Gloucester in 1397, and married Constance of York - great-granddaughter of Edward II and Isabella.

In memoriam: Hugh le Despenser the Younger, executed exactly 680 years ago. Not A Very Nice Guy, but an interesting one. ;) I'll be toasting him with a glass of bubbly later!

15 November, 2006

Edward II in custody 1327: part two, escapes

The reasons for the Dunheveds' great loyalty to Edward II are uncertain (see the post below this one for some biographical details of them). Edward seems to have been the kind of man who repelled many, or most, people with his odd and unkingly behaviour, but in a very few people, he inspired intense loyalty and love. The gang itself was small, but Alison Weir points out that 'there must have been... a network of conspirators throughout the south-west' supporting them. Supposedly, some of the 'great ones of the land' were supporting them - who, is uncertain.

One of these conspirators was Donald, earl of Mar, nephew of King Robert Bruce. Donald was born around 1300, son of Gratney, earl of Mar and Robert Bruce's sister Christina. He was taken to England as a hostage in 1306 with many members of his family, though Edward I ordered that he didn't have to be held in chains, because of his tender age. At some point, he ended up in Edward II's household, where he grew so devoted to the king that he refused to return to Scotland after Edward was forced to release all the Scottish hostages in 1314. Donald took part in Edward's campaign against the Marchers in 1321/22, and was at Bristol with the elder Despenser in October 1326. He managed to flee the city before Isabella and Mortimer took it, and returned to Scotland. He was implicated in the earl of Kent's conspiracy against Isabella and Mortimer in 1330, and was in the Welsh marches not far from Berkeley in June 1327, trying to rescue Edward.

What very few people realise, and what is truly fascinating, is that the Dunheved brothers succeeded in freeing the ex-king Edward II from Berkeley Castle in the summer of 1327. The exact details are unclear - 'shrouded in secrecy', you might say - but that Edward was temporarily free is certain. Somehow, members of the organised and extremely competent Dunheved gang, presumably hiding out in the numerous woods in the vicinity, gained entry to Berkeley Castle in June. Paul Doherty remarks that building work was being carried out on the castle at this time, and that perhaps members of the gang infiltrated the group of workmen. Alternatively, one man may have entered the castle dressed as a priest (as some of the gang were). Once one or several men were in, they could open a postern gate for the others. The looted and ransacked the castle, overcame Edward's guards, and fled outside with Sir Edward of Caernarvon, as he was now known.

The evidence for this extraordinary capture comes from a contemporary letter, written on 27 July 1327 at Berkeley Castle and addressed to the Chancellor, John de Hothum. The author was either John Walwayn, a royal clerk presumably investigating the affair, or Lord Thomas Berkeley himself. The author states that the Dunheved gang had been indicted for 'abducting the father of our lord the King [Edward III] out of our guard, and feloniously plundering the said castle'. Twenty-one men are named. On 1 August, Thomas Berkeley was given special powers to hunt down these men. By 20 August, one of them, William Aylmer, had been arrested at Oxford. Doherty speculates that Aylmer turned King's evidence and betrayed his former friends, as all evidence against him was quashed and he was released. Most of the other gang members were captured. The priests and friars were - illegally - not given benefit of clergy, as they should have been; Isabella and Mortimer had no time for such niceties. Most of the men just disappeared. There's some dispute about the fate of the Dunheveds themselves - Thomas, the friar and Edward's confessor, apparently died in Newgate prison, and Stephen evidently managed to evade capture. It seems likely that he joined the conspiracy of Edward's half-brother, Edmund earl of Kent, in 1330.

Doherty draws attention to an interesting murder case of 1329, before King's Bench. A man named Gregory Foriz was accused of murder; William Aylmer was named as one of his associates, and Henry earl of Lancaster (see my previous post) stood as Foriz's guarantor. This connection possibly points to a deeper conspiracy, involving Lancaster - the greatest magnate in England and a man starting to exercise profound misgivings about the regime of Isabella and Mortimer. He would rebel against them in late 1328.

There's no direct evidence that Edward was ever recaptured. However, as Weir points out, the letter of 27 July makes no reference to capturing Edward, only the men who'd freed him, so presumably he was already back at Berkeley. On the other hand, would Walwayn or Berkeley have dared to put down in writing that Edward was still at liberty? Obviously, Roger Mortimer and Queen Isabella couldn't afford to broadcast the fact that the ex-king was at large.

To judge by indirect evidence, however, it seems that Edward was back at Berkeley by early September (unfortunately...;) Around this time, yet another plot was hatched to free him from Berkeley, by a Welsh lord named Rhys ap Gruffydd, yet another man who would support Kent in 1330. Edward was very popular in Wales, and Mortimer was detested, thanks to his empire-building. Rhys and his uncle had long been loyal supporters of Edward, and Rhys fled to Scotland around the time of Edward's deposition. His plot was discovered on 7 September, when he was betrayed to William Shalford, Roger Mortimer's lieutenant in South Wales. Shalford wrote to Mortimer on 14 September that 'if the Lord Edward was freed, that Lord Roger Mortimer and all his people would die a terrible death by force and be utterly destroyed, on account of which Shalford counselled the said Roger that he ordain a remedy in such a way that no one in England or Wales would think of effecting such deliverance'. [Not the original letter, but from a court case of 1331 when Shalford was accused of being an accessory to Edward's murder.]

On the night of 23 September, nine days after Shalford's letter, Edward III was informed of his father's death...

10 November, 2006

Edward II in custody 1327: part one

Henry was King Edward's cousin, the son of Edward I's brother Edmund Crouchback, earl of Lancaster (1245-1296). He was born in about 1281 and was the younger brother of Earl Thomas of Lancaster, Edward II's most implacable enemy, beheaded in 1322. Through his elder half-sister Jeanne, Queen of France and Navarre, he was also the uncle of Queen Isabella.

Henry, arguably the only person to emerge from the period 1327-30 with any credit, treated the fallen king with respect and honour. In January, Edward was either forcibly deposed, or abdicated voluntarily - it's still not entirely clear which - leaving the new rulers of England with the thorny problem of what to do with the ex-king. Many people were uneasy with the situation of the king being in prison, but if Edward were released, he could revoke his deposition and reinstate himself. The death of Mortimer, and probably Isabella too, would certainly be the result - they had executed the Despensers, and Edward could be vindictive and merciless in revenge. Also, Henry - although an ally of the couple and Isabella's uncle - was a political danger. To ensure his support, Isabella and Mortimer had promised him his brother's earldom of Lancaster, but the huge lands and revenues of the earldom gave him great power, and his brother Thomas had used that power to constantly disagree with and thwart Edward. Although Isabella and Mortimer had needed Henry's support during their revolution, they now had to neutralise him. Custody of the king gave him enormous leverage over them - he could threaten them with Edward's restoration any time he was dissatisfied, and they didn't want Henry to wield the kind of disruptive power his brother had.

To add to their problems, a group of Edward's supporters were plotting to free him from Kenilworth in March 1327. The gang's leaders were the Dunheved (or Dunhead) brothers: Thomas, a Dominican friar and King Edward's confessor, and Stephen, Lord of Dunchurch in Warwickshire. There were contemporary rumours that Edward had sent Thomas to the Pope to secure a divorce from Isabella. While there's no direct evidence of this, it's quite plausible.

The other conspirators were: two men named William Aylmer (one the parson of Donnington Church), William Russell, Thomas Haye, Edmund Gascelyn, William Hull and John Morton. There was a flurry of writs and orders for their arrest, issued by an alarmed Mortimer and Isabella who had numerous other problems to contend with also, but the gang managed to evade capture - and were to cause many more headaches for Mortimer and Isabella later in the year.

In late March 1327, the former Edward II was removed from Kenilworth and sent to Berkeley Castle, in Gloucestershire. It's not clear if Henry of Lancaster agreed to Edward's removal - 'washed his hands of him', in Paul Doherty's words - or if it was forced on him. According to Ian Mortimer's recent biography of Edward III, Roger Mortimer supervised Edward's removal himself, and Henry was furious, though Doherty and Alison Weir claim that Henry was keen to rid himself of the huge responsibility for Edward.

The Lord of Berkeley was Thomas, who was born about 1293/97, and married Roger Mortimer's eldest daughter Margaret in 1319. He and his father Maurice were imprisoned by Edward in early 1322, during Edward's successful campaign against the earl of Lancaster and the Marcher lords, and Maurice died in prison at Wallingford Castle in 1326. Thomas, therefore, had every reason to detest the former king, and given that his father-in-law was now the main power in England, every reason to remain loyal to him. Berkeley had the advantage of being far away from Scotland, where many of Edward's allies were, and also, the Dunheveds were strong in the vicinity of Kenilworth. The disadvantage of Berkeley was its proximity to Wales, where Edward had more friends, but on the plus side, it was remote and secure. Edward arrived there by 6 April 1327 at the latest. Thomas Berkeley and his brother-in-law Sir John Maltravers - Edward's joint jailor - were awarded the princely sum of five pounds per day for the former king's upkeep.

The chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker, several decades later, gives the familiar story that Edward was mistreated at Berkeley, humiliated, half-starved, and incarcerated in a cell above animal carcasses, in the hope that the stench would kill him. However, it's also possible that Edward was treated reasonably well. The records show that he received delicacies such as capons and wine, though it may be that his guards stole them. While it seems highly unlikely that he was treated as an honoured guest, the stories of his incarceration above rotting animal carcasses may be exaggerated. It's difficult to know for sure. One thing that is definite is that Edward never saw his wife or his children again.

In part two, shortly, I'll look at the little-known story of Edward's secret release from Berkeley in the summer of 1327.