Welcome to the site which examines the events, issues and personalities of Edward II's reign, 1307-1327.

15 November, 2022

The Faces of Edward II, Isabella of France, and Others

08 November, 2022

Uterine Suffocation...?

16 October, 2022

Hugh Despenser the Younger Takes Against John Inge, 1322/23

Hugh Despenser the Younger took possession of the lordship of Glamorgan in South Wales, part of his wife Eleanor de Clare's inheritance from her late brother the earl of Gloucester, in November 1317. A number of letters from Hugh as lord of Glamorgan to Sir John Inge, the sheriff of Glamorgan, still survive, the earliest of them written during Edward II's disastrous siege of the port of Berwick-on-Tweed in September 1319 and the last three years later. Three of the letters are printed in the original Anglo-Norman in volume 3 of Cartae et Alia Munimenta quae ad Dominium Glamorgancia Pertinent, others are calendared in English translation in Calendar of Ancient Correspondence Concerning Wales, and one was printed in an 1897 English Historical Review article by W.H. Stevenson, also in the Anglo-Norman original. The originals are mostly held in the National Archives. Most of the letters are very long and very detailed, and reveal several things: that Hugh Despenser the Younger micromanaged the affairs of Glamorgan even when he was far away from his lordship; that he endlessly hectored the unfortunate John Inge and demanded that the sheriff bend over backwards to do everything he wanted; that he was a hard man to please and serving him was a thankless task; and that he felt a certain degree of contempt for the Welsh people.

It's the last of Hugh the Younger's letters to John Inge that I want to look at today, which is printed on pp. 1101-04 of Cartae et Alia Munimenta, vol. 3. Unlike most of his letters to Inge, it's not dated, but from references within the letter it's apparent that it must have been written in the autumn of 1322. Firstly, the Robert Lewer situation was still ongoing, and Edward II ordered Lewer's arrest on 16 September 1322; and secondly, Hugh wrote that he was following up the matter of the forfeited manor of Iscennen, and Edward granted Iscennen to him on 6 November 1322. Part of the letter refers to Hugh's dealings with Edward's niece Elizabeth de Burgh, whom Hugh politely but rather coldly called la dame de Burgh, 'Lady de Burgh', without acknowledging his relationship to her as his wife Eleanor's sister, as would have been usual and conventional.

In the middle of the very long missive, Hugh wrote, seemingly casually before moving on to talk about Robert Lewer, the following hair-raising sentence:

"And know that we trust you more the more you advise us, but we are very worried about having some reason for which we might be prepared to harm you in some way, or for which we might lose the good will which we have for you."

Ouchie. At some point not too long afterwards, though I don't know exactly when - probably in 1323 or 1324 - Hugh Despenser the Younger imprisoned Sir John Inge and all his council in Southwark because of his 'rancour towards him'. He made Inge and six guarantors promise to pay him £300 for Inge's release, and they had handed over £200 of it by the time of Hugh's downfall in November 1326. In February 1333, Edward III respited the remaining £100 on the entirely true and accurate grounds that the debt was "obtained by force and duress". One of Inge's councillors, Thomas Langdon, died while imprisoned by Hugh, and a petition about him presented probably in 1327 when it was safe to talk about the Despensers' many misdeeds also talks of Hugh the Younger's anger towards Sir John Inge (por corouz qil avoit vers mons' Johan Inge). [1]

John Inge was pardoned in early 1327 at the start of Edward III's reign for having adhered to Hugh Despenser the Younger, though one could hardly blame him if he heaved a sigh of relief when Hugh fell from power and was executed in November 1326. [2] For years, John received endless letters from Hugh that basically say "Do this, do that, go over there right now. No, not like that, you fool, like this. I'm keeping a copy of this letter and you'll regret it if you don't do exactly what I say. Don't make me hurt you." After years of falling over himself to do everything that Hugh wanted in exactly the way he wanted it done, this was John Inge's reward: to be threatened with being harmed, then imprisoned with his councillors, because he had angered Hugh in some way. Chroniclers tell us that even the great English magnates were frightened of Hugh Despenser the Younger, and Queen Isabella certainly was. It's not hard to see why.

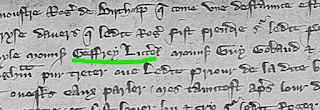

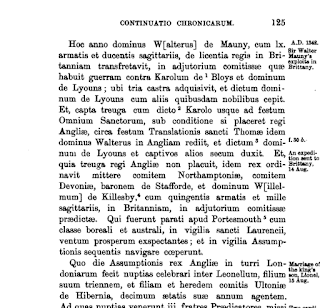

Below, part of Sir John Inge's petition to Edward III requesting that he and his guarantors might be pardoned the remainder of their debt to the late Hugh the Younger.

Sources

1) Calendar of Close Rolls 1318-23, pp. 723-4; Calendar of Patent Rolls 1330-34, p. 404; The National Archives SC 8/176/8753 and SC 8/59/2947.

2) CPR 1327-30, p. 32.

12 October, 2022

The Abduction and Ordeal of Elizabeth Luttrell, 1309

I recently wrote a post about Sir Geoffrey Luttrell (1276-1345), who commissioned the Luttrell Psalter around 1325/30, and his involvement in an attack on Sempringham Priory, Lincolnshire in 1312. Geoffrey's son and heir Andrew, from his marriage to Agnes Sutton, was most probably born around Easter 1313, and they had other children too: younger sons named Geoffrey (b. before 1320), Guy and Robert, and daughter Isabella, who in 1345 was a nun of Sempringham Priory. [1] Geoffrey and Agnes also had a daughter called Elizabeth, who suffered a very distressing experience when she was abducted and raped. It is virtually certain that this was a case of child rape.

Elizabeth Luttrell must have been a good bit older than her four brothers. She first appears on record on 1 June 1309, when she was already betrothed to a young man named Walter, son of Walter Gloucester. [2] On this date, Elizabeth and Walter the younger were granted the reversion of the Lincolnshire manors of Ingoldsby and Skinnand - which is a Deserted Medieval Village - plus lands and meadows in Welbourn and Navenby also in Lincolnshire. Ingoldsby is less than three miles from the Luttrells' chief manor of Irnham and about ten miles from Sempringham Priory, and the Gloucester family also owned manors in Lincolnshire.

Sir Walter Gloucester Senior, Elizabeth Luttrell's father-in-law, died not long before 26 August 1311, and his inquisition post mortem of September that year says that his son and heir Walter was 'seventeen on 15 January last' or 'eighteen on Christmas Day next'. This gives Walter a date of birth around Christmas 1293 or mid-January 1294, though I can't find his proof of age or any mention of it in the chancery rolls. Walter Junior's mother or stepmother was named Hawise, and she outlived her husband by more than twenty years and was still alive in the early 1330s. [3] Walter Jr and his younger brother John attacked Hawise's Lincolnshire manor of Heydour not long before 8 October 1321, and stole twenty oxen, eighteen horses and sixty-six pigs, plus 'jewels and silver vessels'. Wonder what was going on there; apparently a family dispute. [4]

Elizabeth Luttrell gave birth to her son, inevitably also named Walter Gloucester, around Easter 1316, according to her husband's inquisition post mortem. Walter, however, proved his age, ie. twenty-one, sometime before 19 July 1336, which strongly implies that he was born before July 1315. On 10 July 1336, he was said to be 'aged twenty-one years and more'. [5] Walter was only a couple of years younger than his uncle Andrew Luttrell, the eldest of his mother's four younger brothers, and given that Elizabeth gave birth in or around 1315, she must have been born in c. 1300 at the latest. Sometime before 23 July 1315, possibly while Elizabeth was pregnant or had recently given birth, her husband and his brother John were accused of attacking the manor of one William Mortimer in Ingoldsby: 'with a multitude of horse and foot[men]', the brothers besieged William's house, threw stones and shot arrows at the doors and windows, finally gained entrance to the property by setting fires outside the doors, and stole the unfortunate William's goods after tying him up. [6] Hmmmm, I see a pattern emerging here. Walter Gloucester died not long before 20 February 1323 at not yet thirty years old, and on 12 May that year, Hawise founded a chantry for her late husband Walter (d. 1311) and for her son or stepson, having evidently forgiven him for his theft of her livestock in 1321. Elizabeth received her widow's dower on 20 October 1323, and on 7 March 1324, she and her father Geoffrey Luttrell jointly acknowledged a debt of £100. [7]

In the summer of 1309, before she married Walter, something horrible happened to Elizabeth Luttrell. Already living with her future husband's family, she was abducted from somewhere called 'Laund' - I'm not sure where that is, maybe Lound in Nottinghamshire - by John Ellerker, and raped. I don't know how old the unfortunate Elizabeth was when she suffered this ordeal, but she was certainly a child or at the very most in her early teens. Her father Geoffrey was only thirty-three years old in 1309, and her four brothers were still years away from being born.

John Ellerker was a clerk, and Ellerker, presumably where he came from, is a village in Yorkshire, about ten miles from Beverley and thirty from York. There's a huge number of entries in the chancery rolls and elsewhere during the reigns of Edward II and III relating to 'John Ellerker the elder' and 'John Ellerker the younger', who were, oddly enough, brothers. The majority of the entries deal with people acknowledging debts to the two men, and one of them was chamberlain of North Wales at one point. I have no idea if one of them was the man in question or if they were unrelated. It appears that the John Ellerker who abducted and assaulted Elizabeth Luttrell was later the rector of Willingham by Stow in Lincolnshire, became a canon both of Beverley and York in the 1320s, and was a royal clerk. [8] From this entry in the archbishop of York's register, dating to early 1315, Ellerker was illegitimate.

The first piece of evidence for Ellerker's abduction of Elizabeth Luttrell dates to 1 July 1309 ('the Tuesday next after the feast of St Peter and St Paul, 2 Edward II'), when the Close Roll records an '[e]nrolment of agreement between Sir Walter de Gloucester, knight, and John de Ellerker, clerk, concerning the abduction by the said John of Elizabeth, daughter of Sir Geoffrey Luterel, at Laund, she being in the company of Amice de Gloucestre'. [9] The 'Sir Walter Gloucester' named here means Elizabeth's soon-to-be father-in-law, and I assume Amice was the daughter of the older Walter and sister of the younger Walter, and Elizabeth's future sister-in-law. The ill feeling of his victim's father and future father-in-law towards Ellerker was, understandably, so bad that John Langton, bishop of Chichester and chancellor of England, felt compelled to intervene. He persuaded Geoffrey Luttrell and Walter Gloucester the elder to remit not only their ill feeling, but 'all actions, challenges etc' they might wish to undertake against John Ellerker. It appears that Ellerker had become infatuated with Elizabeth, as he had to declare, on pain of paying £1000, that he 'will not claim the said Elizabeth as his wife in court Christian, or ravish or abduct her, or cause her to be ravished or abducted...he has sworn upon the gospels that he will not procure the abduction nor rape of the said Elizabeth, nor induce her to leave the company of the said Walter [Gloucester the elder].'

How Ellerker might claim to be married to Elizabeth when he was in holy orders is not clear to me, and numerous other details of the story are not explained, such as, how exactly Ellerker abducted Elizabeth (on his own or with accomplices?), how a clerk became so dangerously infatuated with a young girl of noble birth, where he took her after the abduction, and how she was freed and restored to her natal family or the Gloucesters. It certainly seems that Elizabeth's father and father-in-law believed that she remained at risk from John Ellerker even after her release. Elizabeth's mother Agnes Sutton and future mother-in-law Hawise Gloucester - I don't know Hawise's maiden name - must also have been deeply concerned and distressed by what had happened to her, but are not mentioned in the record of the agreement. Thanks, fourteenth-century England.

The agreement between John Ellerker and Sir Walter Gloucester the elder does not directly state that Ellerker raped Elizabeth after he kidnapped her, but on 5 August 1309, Edward II pardoned Ellerker 'for the rape and abduction of Elizabeth, daughter of Geoffrey Luterel'. This was done 'at the instance of Hugh le Despenser' and was recorded on the Patent Roll. [10] Which Hugh Despenser was not specified, but at this stage of Edward II's reign, the name 'Hugh Despenser' used alone basically always meant Hugh the Elder (b. 1261), later earl of Winchester, not his son Hugh the Younger, later lord of Glamorgan. I don't know whether Hugh Despenser the Elder had any real connection to John Ellerker, or whether the latter had merely persuaded a well-known courtier and ally of Edward II to use his influence with the king. I did find a connection between Hugh the Elder and Walter Gloucester, the one who died in 1311 and was Elizabeth Luttrell's father-in-law: on 5 February 1309, just months before this tragic situation occurred, Walter was one of the men who witnessed Sir Thomas Gredley granting his manor of Pirton to Hugh the Elder. [11]

As Elizabeth was still named as 'daughter of Geoffrey Luttrell' in July and August 1309, she evidently hadn't married the younger Walter Gloucester yet. I'm not sure what became of her after March 1324, when she and her father acknowledged a joint debt the year after she was widowed, though I have wondered if the Isabella, nun of Sempringham Priory named as Geoffrey's daughter in his will of 1345 might in fact be Elizabeth; the names Isabella and Elizabeth were often used interchangeably. It would hardly seem surprising if Elizabeth sought a religious life in widowhood after experiencing such a horrible attack in her youth. Whatever happened to her, I sincerely hope she found some measure of happiness after surviving such an awful ordeal, though her husband robbed the manors of at least two people and seems to have been pretty wild (to be fair, there's no evidence that Walter Gloucester harmed the people he stole from or was violent). As noted above, John Ellerker, sadly, thrived after his abduction and rape of Elizabeth, becoming a rector and a canon. It strikes me that he might also have been very young in 1309, albeit not as young as Elizabeth: a 'John Ellerker, archdeacon of Cleveland' appears on record several times in 1351. [12] If this is the same man, he was still active forty-two years after 1309, and the situation reminds me somewhat of John Berenger's rape and abduction of Elizabeth Hertrigg in 1318, when they were both about fourteen.

Elizabeth's son Walter Gloucester the third, probably born in 1315, married a woman named Pernell, and they had two sons, John, born around 1 August 1349, and Peter, born c. 1354/55. Walter died on 10 July 1360 and Pernell at the beginning of 1362. Their first son John died sometime in the eighteen months between his father's death and his mother's, probably aged twelve, and Peter Gloucester died on 24 September 1369. Although Peter had married a young woman called Alice who received dower after his death, he was only about fourteen or fifteen when he passed away, and left no children. [13] Unless Elizabeth Luttrell had other children I haven't discovered, her line ended with her two grandsons in the 1360s. Of her younger brothers, Andrew lived to be seventy-seven; Geoffrey seems to have died young; Guy died before their father, but left four sons and a daughter; and Robert became a Knight Hospitaller and was still alive in 1345.

07 October, 2022

A Petition from Blanche of Lancaster, Lady Wake, 1320

Blanche of Lancaster was born sometime in the early 1300s as the eldest child of Edward I's nephew Henry of Lancaster (b. c. 1280/81), later earl of Lancaster and Leicester, and Maud Chaworth (b. 1282). She was born in the reign of her great-uncle Edward I and died between 3 and 11 July 1380 in the reign of Richard II, when she must have been in her mid to late seventies, having outlived her six younger siblings. She was the aunt, and perhaps godmother, of the more famous Blanche of Lancaster (1342-68) who married John of Gaunt and was the mother of Henry IV.

Blanche married Thomas Wake, future Lord Wake of Liddell (b. March 1298), before 9 October 1316, probably not too long before. Edward II fined his ward Thomas £1000 when he found out, as the marriage had taken place without his licence; he had offered Thomas the marriage of Piers Gaveston's daughter and heir Joan, only to find that Thomas preferred to wed Blanche. Edward pardoned Thomas on 9 December 1318, and allowed him seisin of his late father John Wake's lands a couple of years early at the request of his cousin, Thomas's father-in-law Henry of Lancaster. [1] As to why Thomas preferred to marry Blanche of Lancaster, who had a younger brother and five younger sisters (though not all of them had been born by 1316) and was not an heiress, over Joan Gaveston, who was an only child until her half-sister Margaret Audley was born c. the early 1320s and was a sizeable heiress, we can only speculate. Blanche and Thomas Wake were married for over thirty years until Thomas died in 1349, though they had no children (Thomas's heir was his nephew John, earl of Kent, d. 1352).

On 24 April 1320, Edward II gave Thomas Wake permission to go overseas on pilgrimage with two attendants, William Wasteneys and Richard Normanby. Thomas was, however, still at his Lincolnshire manor of Bourne on 6 June 1320, when he made a grant to Sir Roger Belers that was witnessed by, among others, his younger brother John Wake and Wasteneys and Normanby, the men who would accompany him on pilgrimage. [2] Thomas did eventually leave England that year, and as chance would have it, his Lancastrian father-in-law Henry also spent much of the period from 1318 to 1322 overseas. Henry's obscure younger brother John of Lancaster, whose heir he was, died in France before 13 June 1317, and Henry went there in May 1318. On 28 September 1318, he was 'staying in France to claim his inheritance', and on 21 August 1320 was 'staying beyond the seas' until the following June, though he returned to England for a while in November 1320. [3] His wife Maud Chaworth accompanied him (see below for source).

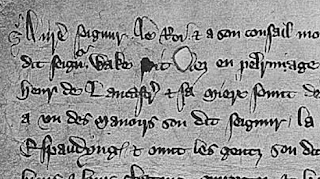

Sometime in 1320, after 6 June and before 24 November, Blanche of Lancaster presented a petition in Anglo-Norman to Edward II and his council, calling herself 'Blaunche Wake, cousin of our lord the king and consort of Lord Wake' and stating that her husband had gone on pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela (seint Jake) with royal permission. [4] She added rather plaintively that 'her father Sir Henry of Lancaster and her mother are overseas, and therefore she remains alone'. Blanche went on to say that one of her husband's manors had been attacked by 'numerous robbers and murderers' from the town of Spalding in Lincolnshire, who had killed some of Thomas Wake's servants and her own, and badly wounded others to the point of death. She did not specify which manor, but Thomas held several in Lincolnshire, including Bourne and Market Deeping, which are both about twelve miles from Spalding. The people from Spalding had also stolen goods and chattels from the manor, and had taken away the dead bodies (les corps de eux q' sont mortz aloignez), an unusual detail which I don't recall seeing in a fourteenth-century petition before. Blanche finished by stating that she and her 'ladies', i.e. her attendants, were so frightened and distressed that they did not dare to stay at the manor, and she begged Edward II and the royal council to help her as soon as possible. Unfortunately, they did not, but only responded that she had no right to an action resulting from the petition. I haven't been able to find any other reference to this attack on a nearby manor by the people of Spalding.

Below, part of Blanche's petition.

In 1320, Blanche was only a teenager, who might have been eighteen but perhaps was as young as fifteen, and obviously felt isolated and afraid with her husband and her parents overseas. Her closest relatives in England were, apart from her younger siblings (assuming they weren't abroad with their parents), her father's cousin the king and her paternal uncle Thomas of Lancaster, earl of Lancaster and Leicester. Thomas of Lancaster isn't mentioned in the petition, and I have no idea if he tried to help her or not. Another close relative was Hugh Despenser the Younger, half-brother of Maud Chaworth, and thus also Blanche's uncle. Hugh was then Edward II's chamberlain and had already become a pretty powerful royal favourite, though I have no idea either if he did anything to help her. I find the petition poignant. Many years later, as a widow in the 1350s, Blanche, Lady Wake had an awful feud with Thomas Lisle, bishop of Ely, and gave as good as she got, but in 1320 she was young and vulnerable.

Thomas, Lord Wake was back in England by 24 November 1320 when he settled two of his own manors in Cumberland and Yorkshire on himself and Blanche jointly, and Henry of Lancaster had also returned by 16 November 1320. [5] I wonder if this isn't a coincidence, especially as Henry had originally intended to remain overseas until June 1321, and perhaps Blanche sent messengers to her husband and her father and they both hurried home. It kind of amazes me that Blanche lived for another sixty years after the events she described in her petition.

Sources

1) CPR 1313-17, p. 553; CPR 1317-21, pp. 43, 251-2; CCR 1313-18, p. 413; CIPM 1291-1300, no. 597 (John Wake's IPM; CIPM 1352-60, no. 219 (Thomas Wake's); CIPM 1377-84, nos. 438-45 (Blanche's).

2) CPR 1317-21, pp. 440, 494-5.

3) Foedera 1307-27, p. 334; CPR 1317-21, pp. 145-6, 153, 217, 503, 524, 548; CPR 1321-24, p. 69.

4) The National Archives SC 8/87/4346.

5) CPR 1317-21, pp. 524, 531.

24 September, 2022

Marriage Rights

18 September, 2022

Sir Geoffrey Luttrell and an Attack on Sempringham Priory, 1312

11 September, 2022

Book Giveaway: Sex and Sexuality in Medieval England

My new book Sex and Sexuality in Medieval England is out now! It's part of a series on sex and sexuality from Pen&Sword that includes Tudor England, Stuart Britain, and Victorian Britain.

I have TWO free copies to give away to readers! You can live anywhere in the world, as long as you have a postal address I can send the book to. Please contact me with your email address or some other means of getting in touch with you, so I can notify the winners. To enter the draw, do one of the following: leave a comment here on the blog; comment or message me on my Edward II Facebook page or comment on my Twitter page; email me at edwardofcaernarfon(at)yahoo(dot)com; or if we're friends on Facebook or follow each other on Twitter, you can message me there. Best of luck! Deadline is midnight BST on Sunday 25 September. And please remember, if you leave a comment on the blog, give me an email address or some other way of contacting you. If I can't contact you, I have no way of telling you that you've won!

04 September, 2022

The Abduction of John Chaucer, 1324

Geoffrey Chaucer, the poet, b. c. 1342/44.

One thing we do know is that Mary and Richard Chaucer asked for damages of £300 and were awarded £250, a massive sum in an age when £5 was a normal yearly income. Geoffrey Stace sent a petition to the king in the late 1320s or 1330, complaining that the lands of John Chaucer's inheritance were only worth £1 per year and that therefore £250 was an ureasonably excessive amount. Incidentally, the Second Statute of Westminster in 1285 set the punishment for abducting a child (whether male or female) whose marriage belonged to someone else at two years' imprisonment, as long as the person restored the child still unmarried, or paid what the marriage was worth. Otherwise, the punishment was either life imprisonment or abjuration of the realm, i.e. permanent exile from England. [6] It was taken very seriously. John's stepfather and guardian Richard Chaucer, and John's older half-brother Thomas Heyron, apparently exacted revenge on Geoffrey Stace and Agnes after the abduction. They travelled from London to Ipswich, a distance of about 70 miles, and stole goods worth £40 from Agnes Westhale/Stace's house, or so the indignant Agnes claimed in 1325. [7] John Chaucer was around twelve or fifteen in 1324/25, and his Heyron half-brother, given that his father died sometime around 1303/04, must have been in his early twenties or older. There is much evidence that the two half-brothers were very close and often acted together.

On 16 December 1330, eighteen-year-old Edward III - who had recently taken control of his own kingdom from his mother Isabella of France and Roger Mortimer - sent a letter to Sir Geoffrey Scrope, one of the chief justices of the King's Bench and ancestor of the Scropes of Masham (Henry, Lord Scrope of Masham, executed by Henry V in 1415 after the Southampton Plot and mentioned by Shakespeare in his play about Henry, was Sir Geoffrey Scrope's great-grandson). The letter, stating that John Chaucer was now 'of full age', is printed in the Calendar of Close Rolls 1330-33, pp. 90-91, and was almost certainly a response to Geoffrey Stace's petition. Geoffrey Stace had been detained in the Marshalsea prison in London because of his 'trespass against the king's peace', as well as being held liable for the massive sum of £250, and Edward ordered his release. The Letter-Books of London (vol. E, pp. 218-19, 226, 237, 239-40) show that several inquisitions were held in the city in 1328, one of which was to determine whether Geoffrey Stace, his relative Thomas Stace and his servant Lawrence had committed perjury, and the whole thing dragged on for several years, as often happened in medieval court cases (and the delay in this one was worsened by the dramatic events of 1326/27 when Edward II was forced to abdicate in favour of his son). The 16th of December 1330 was six years and thirteen days after John Chaucer's abduction had taken place.

A few years after his abduction by his aunt and uncle, John Chaucer married Agnes Copton, and they became the parents of Geoffrey Chaucer. I wonder if it's a coincidence that Geoffrey bore the same name as his father's uncle Geoffrey Stace, or if the latter was his great-nephew's godfather and John Chaucer was doing his best to bury the hatchet. Geoffrey Stace was still alive in February 1344, and Geoffrey Chaucer had probably been born by then. [8]

15 August, 2022

15 August 1342: Wedding of Lionel of Antwerp and Elizabeth de Burgh

Edward III and Philippa of Hainault's third, but second eldest surviving, son Lionel of Antwerp married the heiress Elizabeth de Burgh in the Tower of London on 15 August 1342, the feast of the Assumption. The date is given in the Calendar of Select Plea and Memoranda Rolls of the City of London (vol. 1, 1323-64, p. 153), and confirmed in the Continuatio Chronicarum of the royal clerk Adam Murimuth (ed. E.M. Thompson, p. 125).

Born in Antwerp on 29 November 1338, Lionel was still only three years old when he married, and it therefore seems highly unlikely that he would have had any memories of his own wedding. On 5 May 1341, Edward III had issued a 'grant that Elizabeth, daughter and heir of William de Burgo, late earl of Ulster, deceased, who held of us in chief, shall marry our dearest son Lionel [Leonello filio nostro carissimo] ... when he is old enough', and evidently being three years and eight and a half months old was deemed 'old enough'. [CPR 1340-43, p. 187; Foedera 1327-44, p. 1159] Incidentally, Lionel's name was spelt Leonell or Lyonell in his own lifetime, revealing its contemporary pronunciation: as in Lionel Messi, not Lionel Ritchie.

As for Elizabeth de Burgh, she was almost six and a half years older than her bridegroom. According to the inquisition post mortem of her father William 'Donn' de Burgh, earl of Ulster, Elizabeth was born on or close to 6 July 1332: in early August 1333, she was said to be 'aged one year on the eve of St Thomas the Martyr last'. [CIPM 1327-36, no. 537] Her father, himself born on 17 September 1312, was not yet twenty when his daughter was born and not yet twenty-one when he died on 6 June 1333, and was a minor in the wardship of the king, his first cousin once removed Edward III, who in fact was two months younger than he was. Elizabeth was surely named in honour of her paternal grandmother Elizabeth de Clare (1295-1360), Lady de Burgh, Edward II's niece. The older Elizabeth mentioned her granddaughter, who was her principal heir, in her will of September 1355, but only thus: 'Item, I bequeath to Lady Elizabeth my [grand]daughter, countess of Ulster, all the debts which my son, her father, owed me on the day he died' (It'm je devise a dame Elizabeth ma fille countesse Dulvestier tote la dette qe mon filz son piere me devoit le jour qil morust). Ouchie.

Elizabeth was her father's sole heir and was his only child, or at least his only child who survived infancy. She alone was named as his heir in his inquisition post mortem. There is some evidence, however, that William de Burgh's widow Maud of Lancaster (c. 1310/12-1377) might have given to birth to posthumous twins. On 16 July 1338, there's a reference on the Patent Roll to 'Isabella, daughter and heir of William, late earl of Ulster'. [CPR 1338-40, p. 115] It is quite possible that this means Elizabeth, as Isabel(la) was a variant of the name and they were sometimes considered interchangeable, though it does seem that by this stage of the fourteenth century they were thought to be separate names, and every other reference to Elizabeth de Burgh that I've found calls her Elizabeth, not Isabella. And on 6 April 1340, Edward III granted the marriage of 'Margaret, daughter and heir of William de Burgh, earl of Ulster' to his sister and brother-in-law Eleanor of Woodstock and Reynald II of Guelders, to use for their second son Eduard (b. 1336). [CPR 1338-40, p. 445] This might, however, be a scribal error; it wasn't unusual for clerks to get names wrong sometimes. Assuming that these two girls ever did exist, they must have died young, and if Maud of Lancaster was pregnant when her husband died in 1333, the jurors at his IPM hadn't heard about it. Assuming that 'Margaret' was an error for Elizabeth, at some point between 6 April 1340 and 5 May 1341 Edward III changed his mind and decided that Elizabeth should marry his son rather than his nephew.

Elizabeth de Burgh was ten when she wed three-year-old Lionel. She was related to him via both her parents: via her father she was a great-great-granddaughter of Edward I, who was Lionel's great-grandfather, and via her mother Maud of Lancaster, she was a great-great-granddaughter of Henry III, also Lionel's great-great-grandfather. Via Maud of Lancaster, Elizabeth was related to pretty well everyone: Henry of Grosmont, first duke of Lancaster, was her uncle, and her first cousins included Henry IV's mother Blanche of Lancaster (b. 1342), Henry Percy (b. 1341) and Thomas Percy (b. c. 1343), earls of Northumberland and Worcester, John, Lord Mowbray (b. 1340), Henry, Lord Beaumont (b. 1339), and Richard Fitzalan, earl of Arundel (b. c. 1347) and his sisters Joan, countess of Hereford and Alice, countess of Kent. Elizabeth was the eldest grandchild of Henry of Lancaster, earl of Lancaster and Leicester, who died in 1345 when she was thirteen, and her much younger half-sister was Maud Ufford (b. late 1345 or early 1346), who married Thomas de Vere, earl of Oxford (d. 1371) and was the mother of Richard II's 'favourite' Robert de Vere, earl of Oxford (1362-92). Elizabeth's namesake great-aunt Elizabeth de Burgh, one of the many sisters of her grandfather John de Burgh (d. 1313), was queen consort of Scotland as the wife of Robert Bruce, and was the mother of David II, king of Scotland (1324-71). Isabella of France was, I assume, the person responsible for granting William de Burgh's marriage rights to her uncle Henry of Lancaster, earl of Lancaster and Leicester, at the start of her son Edward III's reign on 3 February 1327. [CPR 1327-30, p. 8] Sometime that year William married Maud, third of Henry's six daughters, who was close to his own age, so this was a wedding of two people both aged about fourteen or fifteen at the time. Their daughter Elizabeth was born five years after their wedding.

According to the Medieval Lands project on the Foundation for Medieval Genealogy site, Lionel and Elizabeth had another wedding ceremony at Reading Abbey on 9 September 1342 three weeks after they married in the Tower, but no primary source is cited, so I can't confirm this. Edward III was nowhere near Reading in September 1342, spending all that month in Sandwich and Eastry in Kent. By contrast, he was certainly at the Tower of London on 15 August 1342.

Elizabeth de Burgh, countess of Ulster and later duchess of Clarence, gave birth to her only child, Philippa of Clarence, countess of March and Ulster, on 16 August 1355. Rather astonishingly, that was the day after her and Lionel's thirteenth wedding anniversary, and Lionel was still only sixteen when his daughter was born (Elizabeth was twenty-three). I doubt it's a coincidence that Philippa was born thirty-seven weeks after her father's sixteenth birthday on 29 November 1354. The Medieval Lands site states that the marriage was consummated in 1352, which to be honest I find a bit of a bizarre thing to claim, as I'm not sure where something like that would be recorded. Lionel turned fourteen on 29 November 1352, and for sure some noble and royal boys were allowed to consummate their marriages at fourteen, but the only way we know that is because a pregnancy resulted. To give an example, Lionel of Antwerp and Elizabeth de Burgh's grandson Roger Mortimer, fourth earl of March, was born on 11 April 1374, and his and Alianore Holland's daughter Anne Mortimer, countess of Cambridge, was born on 27 December 1388.

Neither of the child-couple who married in August 1342 lived long lives. Elizabeth de Burgh died on 10 December 1363 at the age of thirty-one, and Lionel of Antwerp died in Italy on 17 October 1368 a few weeks short of his thirtieth birthday, having been briefly married a second wife, the Italian noblewoman Violante Visconti. Elizabeth was outlived by her mother Maud of Lancaster, dowager countess of Ulster, who became a canoness after the death of her second husband Sir Ralph Ufford and died on 5 May 1377, a few weeks before her kinsman, Lionel's father Edward III. The couple's daughter and heir Philippa of Clarence gave birth to her eldest child Elizabeth Mortimer in February 1371 when she was fifteen and a half, and if Lionel had still been alive then, he would have become a grandfather at just thirty-two years old. If he'd still been alive at the end of 1388, when Anne Mortimer was born, he would have become a great-grandfather a month after he turned fifty.

13 August, 2022

No, Isabella of France Was Not a 'Pawn'

Let's take a look at how Isabella herself viewed royal marriages. She purchased the marriage of twelve-year-old Philippa of Hainault from Philippa's father Willem, count of Hainault and Holland, in August 1326, in exchange for Willem providing troops and ships for Isabella's invasion of England. The third daughter of a mere count was hardly a great match for Isabella's son Edward III, son of a king and grandson of two more kings. As for poor Philippa, she got to be exchanged for ships and mercenaries. Is it possible to have a less romantic start to a marriage, albeit one that ended up being very close and loving? It's hardly any wonder that, later in life, Philippa herself told the chronicler Jean Froissart that Edward III chose her as his future wife from among her sisters. Froissart repeated this pleasant little tale uncritically as though it were gospel truth, as have numerous later writers, but it's nonsense on stilts, and represents Queen Philippa decades later looking back on her early life through rose-coloured spectacles. Philippa's older two sisters Margaretha and Johanna had both married in February 1324 - a double wedding in Cologne with two German bridegrooms, Ludwig of Bavaria and Wilhelm of J[]lich - and the only other Hainault sister alive in the summer of 1326, Isabella, was little more than a toddler at the time. She was obviously far less suitable as a bride for the nearly fourteen-year-old Edward of Windsor than twelve-year-old Philippa was, but if anything had happened to Philippa before her and Edward's wedding, he would indeed have married Isabella instead. If anything had happened to both Hainault sisters, the replacement would have been their cousin [], daughter of the count of Hainault's younger brother Jehan de Beaumont. If anything had happened to Edward III before he married Philippa, she would have married his younger brother John of Eltham instead. To imagine that the whims and choices of adolescents had anything to do with power politics at this level, and with the supremely hard-headed and unromantic negotiations between the queen of England and the count of Hainault, is frankly absurd.

07 July, 2022

Book Giveaway: Fourteenth-Century London

My new book, London: A Fourteenth-Century City and Its People, is out now! It's a social history of the city and its inhabitants from 1300 to 1350, with dozens of short chapters on numerous aspects of life, such as Health, Houses, Food, Misadventure, Gardens. Privies, Belongings, Assault, Murder, and many others.

If you lived in London in the fourteenth century and a physician diagnosed you with tisik or a posteme, what were you suffering from? What were penitourtes, evecheping and deodand? What jobs did women called cambesteres. callesteres and frutesteres do? If you were accused of being a rorere or a pikere, was this a good thing or not? What was the murder rate like in fourteenth-century London and what happened to criminals? What happened to the drunk and disorderly? How much would you have to pay to rent a house in London, and what would your accommodation be like? What did people do in their spare time? What did they eat and drink, and where? The answers to all these questions and hundreds more are in the book!

I have TWO free copies to give away to readers! You can live anywhere in the world, as long as you have a postal address I can send the book to. Please contact me with your email address or some other means of getting in touch with you, so I can notify the winners. You can either leave a comment here on the blog, on my Edward II Facebook page or on my Twitter page, or you can email me at edwardofcaernarfon(at)yahoo(dot)com, or if we're friends on Facebook or follow each other on Twitter, you can message me there. Best of luck! Deadline is midnight BST on 20 July.